When you enter a Tibetan shrine , you see objects lit by the flicker of candles, hear the sounds of chanting, and inhale the smell of incense. We are trained to look at art, but these objects have lives and relationships with humans that are contingent on all of our senses. In a museum we typically prioritize sight when interpreting objects, but how is it possible to consider, to a fuller extent, our multifaceted sensory engagement with the world?

The Rubin Museum of Art’s exhibition The World Is Sound departs from a pure focus on the visual and ventures into the power of sound and the practice of listening. It considers sound as an integral dimension of the works in the Museum’s collection of historical art from the Himalayan region, many of which were designed as tools in Tibetan Buddhism for helping devotees escape from the cycle of death and rebirth (samsara) and to attain liberation (nirvana). This same theme pervades the work of certain contemporary artists, who take the activity of listening as an opportunity for a radical reimagining of one’s relationship to the world. The juxtaposition of these historical and contemporary works of art elicit surprising connections””all of the art in the exhibition perceives the sense of hearing and sound as tools for removing entrenched modes of thinking, frequently moving beyond conceptions of an individual self and toward expressions of existence as collective experience. They draw attention to our embodied experience of the world, whether it is through a Buddhist practitioner’s recitation of a mantra or a contemporary artist’s electronic transformation of the voice. They also equivocate: are sounds inseparable from their sources and the political and historical circumstances that produce them? Can they instead be regarded as methods for thinking through the fleeting nature of human life and humankind’s relatively recent arrival in the universe, forging non-human-centric perspectives? Are these conceptual concerns equivalent to the spiritual concerns of religion? These are some of the questions that arise when we examine the historical and contemporary art brought together in this exhibition.

The Buddha emphasized the importance of listening in his earliest teachings and methods. He did not write a single word of his sermons during his lifetime (ca. 563-483 bce). He spoke them. In the year after the Buddha’s death, a close follower (often identified in Mahayana literature as his relative Ananda) gathered together five hundred monks in Rajgir, eastern India, and recited all of the Buddha’s discourses from memory. The monastic community (sangha) then approved them as the authentic teachings of the Buddha (dharma). For hundreds of years after this event the Buddha’s teachings still were not written down but transmitted orally in memorized musical chants. It was only around the first century that Sri Lankan Buddhists committed the Buddha’s teachings to writing, codifying them in treatises called sutras, or sayings of the Buddha. The Mahayana sutras stress the importance of listening as a means of receiving wisdom. They are written from the perspective of Ananda, who begins each new teaching with the words “evam maya srutam, or “Thus did I hear.”1 The Buddha’s words were not considered a divine revelation; rather they contained kernels of eternal truth that all humans might ultimately understand.

Within the Tibetan Buddhist tradition the power of the word finds its expression in mantras: syllables or formulas chanted aloud or silently as instruments for transforming consciousness, removing obstructive karma, and attaining liberation. The importance of these practices is embedded in the religion’s name, Mantrayana Buddhism, a major offshoot of Mahayana Buddhism. Together with diagrams of cosmology (mandala) and ritual hand gestures (mudra), mantras symbolize religious truth, which the practitioner may use to attain liberation in a single lifetime””a synchrony of body, speech, and mind. The Mani mantra to the bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvara is believed to contain all of the Buddha’s teachings in just six syllables and is one of the most important and widely used mantras in Tibetan Buddhism. By chanting “OM MANI PADME HUM” repeatedly, practitioners connect their minds to that of the bodhisattva and focus on compassion for all sentient beings. The mantra may be produced vocally or mentally and is accompanied by visualization of the deity, a practice that aids the devotee in understanding the truth of compassion and attaining liberation. To a Buddhist devotee, an image of Avalokiteshvara is an embodiment of this mantra. In some representations, Avalokiteshvara appears in a form known as Shadakshari, or “Six Syllables,” a name that makes this connection explicit by referring to the six syllables of the Mani prayer.

The voice is vital to Buddhist practice. Long choral chants preserve Buddhist teachings and are fundamental to liturgical traditions, serving as the primary means of transmission and information technology. While vocal chanting is common to all of the diverse Buddhist traditions, the use of instruments and attitudes toward music vary considerably. The ritual and musical practices in Tibetan Buddhism are some of the more elaborate among these traditions. Instrumental music is required on almost every ritual occasion as it is considered an offering intended to please the deities. As with mantras, it is either physically played or mentally produced. A full ensemble consists of two types of cymbals, double-headed frame drums, handbells, hourglass drums, conch-shell trumpets, long trumpets, oboes, and bronze gongs. Monks and nuns play these instruments on a daily basis in ceremonies, frequently accompanying choral chants. Apart from pleasing the deities, music guides the practitioner toward the recognition that phenomenal existence is impermanent and transitory and ultimately toward the transcendence of desire and one’s sense of self.

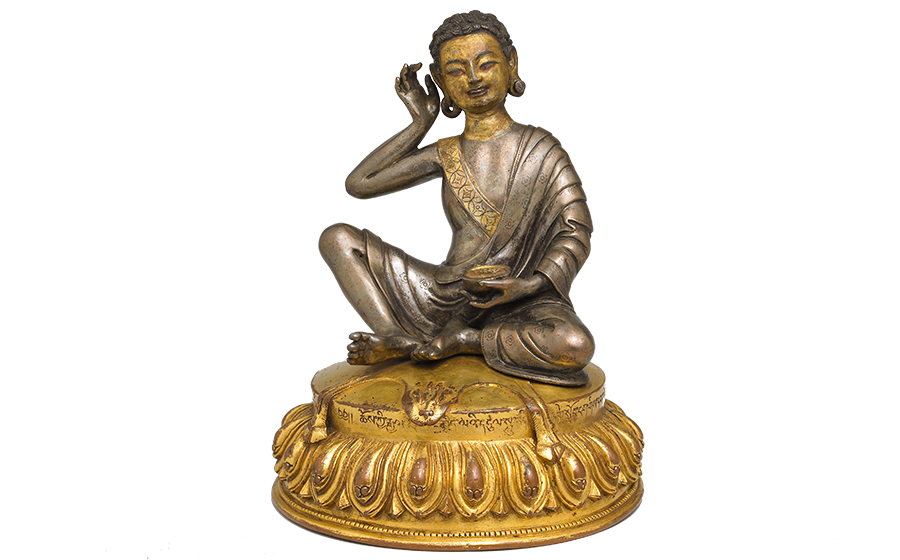

The importance of listening is also expressed in the iconography of images such as that of Milarepa, the eleventh-century Tibetan poet and meditation master. In a gleaming sculpture made in the fifteenth or sixteenth century, he is shown listening with his entire body. His head is cocked, leaning into his cupped right hand, fingers curled gently, suggesting that he hears even the slightest sound. His smiling lips gently part, suggesting that he is simultaneously singing and listening to his own voice, vividly embodying the idea that one may gain wisdom through listening. The story of Milarepa’s life recounts dramatic events and demonstrates that even a great sinner can attain liberation from rebirth in a single lifetime. After murdering thirty-five people with black magic, Milarepa’s remorse compelled him to seek out his guru, Marpa, who successfully instructs him to commit to a life of devotion, isolation, and meditation. During those years of meditation he realized fundamental Buddhist truths and spontaneously composed scores of great songs of awakening (gur) that extol the Buddha’s teachings. These songs describe meditation experiences, dreams, and realizations, and they were Milarepa’s primary means of teaching his disciples.

In one of these songs Milarepa reflects on a dream in which he attempts to plow impermeable earth and almost gives up until Marpa appears and instructs him to persevere. He does, resulting in bounteous crops. His song interprets this dream as a metaphor for overcoming difficulties on the path to liberation:

I clear away stones of unwholesome character

And pull up weeds without pretense.

From ripened ears the truth of actions and results,

I reap the harvest, a superb life of liberation.2

The World is Sound brings together a selection of artists whose work, knowingly or unknowingly, intertwines with Buddhism. Some of the artists are practicing Buddhists or maintain other kinds of spiritual practice, while others are devoutly secular. What all share in is their resistance to entrenched modes of thinking and their search for alternate systems to process the human experience, a phenomenon that might be compared to the Buddhist effort to escape samsara. All the artists focus their awareness through listening and consider the body as a permeable conduit for connecting with the world. They also treat sound as a medium, similar to paint or charcoal, but unlike these latter media it is understood that the sonic cannot be confined to a specific location or even time. As philosopher Christoph Cox writes in his forthcoming book Sonic Flux: Sound, Art, and Metaphysics, many works of contemporary sound art consider the “notion of sound as an immemorial material flow to which human expressions contribute but which precedes and exceeds those expressions.” In this definition of the sonic, it is inherent that sound is not isolated to the sense of hearing, but extends across multiple registers of sensory experience and conceptual thinking.

The composer and artist Eliane Radigue began experimenting with feedback and tape loops in the late 1960s. Trained by the founders of of musique concrète, Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, Radigue ultimately rejected the form, developing what would become known as her signature style of long-duration or drone sound. Schaeffer and Henry considered Radigue’s work an affront to their new genre. While the reasons for their displeasure are unclear, it is possible that the fathers of the new genre took issue with the philosophy Radigue’s sound espoused, and considered it oppositional to their own. While musique concrète blended unrelated sounds together and suggested that sounds could possess life independent of their sources, Radigue’s undulating drone insisted on a fundamental and universal sonic connectivity. Several years later Radigue would find spiritual grounding for the formal qualities of her music in Tibetan Buddhism, which teaches that interrelatedness is one of the primary conditions of reality.

Radigue became one of the first artists to create site-specific sound installations. She developed the concept for labyrinthe sonore, or sound maze, which will find its ultimate iteration in the exhibition as le corps sonore, or sound body, a collaboration realized with the artists Laetitia Sonami and Bob Bielecki. Carefully choreographed on the ARP 2500 synthesizer, her drone sounds slowly modulate and move over us, bringing our awareness to the continually changing, immersive nature of our shared sonic reality. In an interview with the Rubin, Radigue commented that the main purpose of her work is for the listener “to awaken to the music within themselves.” “We should give ourselves over to the sounds,” she says, “be open to the sounds, listen to what is resonating within ourselves.” In conversation she interweaves metaphors of water and soundwaves with the directive to detach from the ego””a concept that verges on a kind of spiritual philosophy, reminiscent of Milarepa’s aim to awaken the awareness of the dharma in others through song. When I ask how she would guide a visitor through le corps sonore she spontaneously composed the following lyrics:

Just leave your body floating in the wave

So leaving the mind

The spirit floating in the sound

Check what happens

Radigue met sound artist Laetitia Sonami in the late 1970s, just as Radigue was beginning her Buddhist practice. Then a young artist newly acquainted with electronic music from a yearlong stint at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Sonami would become Radigue’s longtime student and collaborator. Perhaps not coincidentally, Sonami met Radigue the same year that she met her own Tibetan Buddhist guru, Sakya Trizin. Sonami and Radigue’s shared interests of electronic music and Buddhism, and identities as women within a male-dominated musical culture, ushered their close bond. A few years later the artists were close enough that Sonami’s brother-in-law, Lama Kunga Rinpoche, performed on Radigue’s Songs of Milarepa. Although the two artists have a different aesthetic, their sonic philosophy has much in common, perhaps informed by their Tibetan Buddhist practice. When Sonami describes working on compositions with Radigue, she evokes images of guru-student transmission replete with visualization exercises. As Sonami relates the process: “A lot of music is oral transmission”¦.[Radigue] asks people to play; they bring a palette of technique and then she listens. She says you have to choose an image, the image is your score.”

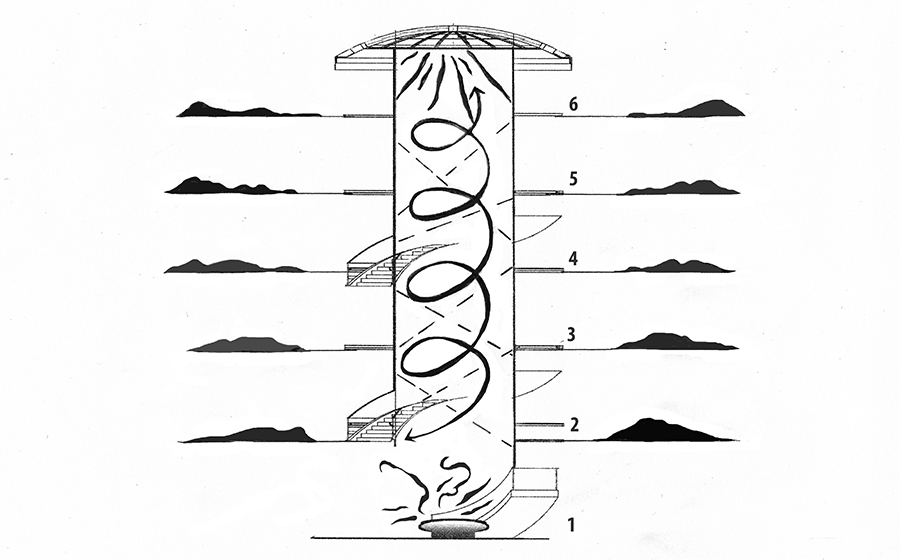

Le corps sonore is in many ways the culmination of these efforts, taking previous installations of the piece skyward. Radigue, Sonami, and Bielecki use the Rubin’s central architectural element (a spiral staircase) as the score and spine of the composition. At the base Bielecki and Sonami generate a reflective pool that transmits worldly sounds such as mantras, environmental field recordings, and voices. As visitors travel upward, they move through five tracks of Radigue’s subtle drone (originally made for labyrinthe sonore). In doing so they leave behind the mundane, much like the desired effect of repeating a mantra. Bielecki, a renowned sound engineer, has precisely programmed the vertical movement of the sound so that it moves up and down all six floors, periodically enveloping the listener and then fading into nothingness, emphasizing the in-between state of Radigue’s sound. Bielecki’s longtime interest has been in measuring and mapping the threshold of hearing and “of finding the place where hearing becomes imaginary.” The verticality of le corps sonore presents a challenge to typical listening because our ears usually localize sound from left to right and not from above and below. The work thus encourages increased focus and an expanded definition of listening to encompass the entire body. To fully absorb the piece, Bielecki states that, “It would be nice to have a third ear on the top of your head.” The immersive and ephemeral qualities of sound are thus discovered by connecting bodily movement to listening, awakening the listener to their own existence as part of a universal acoustic stream.

The subtlety and ephemerality of the sounds in le corps sonore prepare the listener for understanding a core tenet of Buddhist philosophy that flows through the works of art in the Rubin’s collection. In Tibetan Buddhism music is a metaphor for change and impermanence, the primary conditions of reality for the Buddhist practitioner. The ethnomusicologist Sean Williams writes that “when a person performs Buddhist music as part of a crowd of chanters, the individual self disappears into the sangha, or community, eliminating the problem noted by the Buddha himself of attaching importance to one’s individual voice.”3 Musical symbolism also infuses Buddhist teachings, and as ethnomusicologist Ter Ellingson remarks, the “act of proclaiming the Buddhist teaching is historically known as “˜sounding the drum of the Dharma,'” 4 drawing sonic parallels between the instrument’s and the dharma’s clear and authoritative properties. Similarly, early Indian texts liken the tuning of the mind in meditation to the tuning of the vina, a lute-like stringed instrument.

The Buddhist attunement toward sound, impermanence, and minimizing the individual in favor of the collective continues to have a significant impact on certain strains of contemporary art, inspiring different perspectives on listening and being in the world. The late composer Pauline Oliveros (a dear friend of Radigue’s and mentor to several artists in the exhibition) pioneered Deep Listening, an institute, philosophy, and a set of practices that focus awareness on the act of listening as a tool to discern both individual and collective consciousness. For Oliveros listening is the basis of creativity and culture and provides information about how we direct our attention. It is also a form of activism that has the potential to transform the consciousness of groups and individuals. To gain insight into the process of listening, Oliveros devised the Sonic Meditations, a series of written instructions for individuals and groups, often gesturing to Tibetan Buddhist imagery such as mandalas as a point of departure for her exercises. The freedom of listening opens other artists to the fertile potential of sound for reimagining philosophical and political notions of selfhood. Jules Gimbrone, one of the artists featured in the exhibition, regards sound art as a method for subverting normative visual culture. The sonic is a metaphor for the fluid self that defies reification into discrete identities, whether of gender, race, or anything else. Gimbrone states that “Sound is the most queer medium in the sense that it is both physical and uncontainable and doesn’t have the bounds that other forms do.” Listening thus offers opportunities for transformation of individual and societal cultural codes.

Within Tibetan Buddhism the fluidity of sound extends from life into death. Listening may guide the Buddhist practitioner toward liberation and away from the cycle of rebirth. Tibetan Buddhist death rituals include the recitation of texts that guide the consciousness of the deceased through three intermediate states (bardos) that lie between death and rebirth. After death the deceased’s relatives gather to pray for swift release from the bardo. Texts are read aloud to the deceased that describe colors, lights, sounds, and peaceful and wrathful deities encountered while navigating these liminal states over a total of forty-nine days. The ritual also seeks to rid the deceased of fear and liberate the deceased entirely from the cycle of death and rebirth through the recognition that everything encountered in the bardo is a vision of their own mind. For the ritual to be effective, the deceased must have studied the recited text during their own life with the assistance of a teacher.

There is an acute connection between hearing, understanding, and liberation from rebirth. One of the most widely distributed ritual texts, popularized in the West as “The Tibetan Book of the Dead,” expresses this connection and the centrality of listening in its title, Bardo Thodrol, which translates as Liberation upon Hearing in the Intermediate States. Although rebirth is not the ideal outcome of a deceased individual’s journey through the bardo, for the living there is some comfort in knowing that, with guidance, practice, and attention, it is possible to be reborn as a human and to have another opportunity to attain liberation.

The bardos are not limited to the afterlife, and in fact we all reside in the fourth bardo, which lasts from our births until our deaths. Within this bardo of life there are more bardos still, comprising dreams and meditation. These are intermediate states in which consciousness is at its most fluid, where we are most attuned to the ceaselessly occurring transitions that structure our daily life. Listening for these gaps, we find uncertainty, and within this uncertainty exists the space to reflect and change. Writing about music, the Tibetan scholar and leader Sakya Pandita (1182-1251) implies that listening can aid an individual, no matter their stage or position in life, expressed by the following:

For the faithful, an offering, and

For the hungry, a means of livelihood, and

For the passionate, a swaying of the mind””

All these arise from skill in music. 5

These teachings continue to resonate in the present, spreading far beyond their historical Tibetan locale and through unexpected paths of transmission. What would happen in our world if everyone listened to them?

About the Contributor

Risha Lee is the curator of The World Is Sound. She is a graduate of Harvard College, and holds a Ph.D. in Art History from Columbia University. Her work has focused on artistic connections and encounters that traditionally have fallen under the rubric of Asian art but defy easy categorization. She has taught a variety of art history courses at Columbia University and the American University of Beirut, and is currently an independent curator and writer living in Brooklyn.