Is the Rubin Zen?

In the hustle and bustle of New York City life, all of us are trying to find those little moments of zen. At the Rubin, many visitors come to do just that, whether it’s by joining a session of Mindfulness Meditation or by quieting the mind in the Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room. But can you really describe the Rubin and its collection as “zen”? That depends on what you mean. The concept has become so popular in American culture that its meaning has changed. Here’s why you might think again before calling the Rubin “zen.”

A Brief History of Zen in America:

For many people, the term “zen” is synonymous with Buddhism. However, Zen is actually only one of many different Buddhist traditions. The specific sect of Zen Buddhism was the first to take root in the West, which helps explain why the connection between the idea of Zen and the religion of Buddhism in America is so strong.

The first formal introduction of Zen to America was likely during the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, where Zen teacher Shaku Soen spoke at the World Parliament of Religions. By the 1950s and 60s, several Zen Buddhist masters began to immigrate to the United States, establishing major Zen centers in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Just a few years later, members of the counterculture movement of the 1960s like Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, and Jack Kerouac would study at these centers, and later incorporate Zen teachings and terminology into their writing. These texts helped Zen expand into American culture and thought.

So What Does Zen Really Mean?

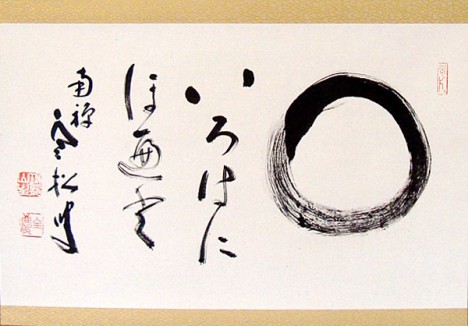

“Zen” is a common word used by many to describe anything or anyone who seems calm and grounded, but what does the word actually mean? Though “zen” is a Japanese word, the Buddhist tradition called Zen actually originated in China under the name chan during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 C.E.). The term “chan” itself is the Chinese version of the Sanskrit dhyana which is often translated into the word, “meditation”.

So is the Rubin Zen?

The Rubin’s collection features the artworks of Himalayan Asia, which traditionally practices a different type of Buddhism known as Vajrayana, Tantric, or Esoteric Buddhism. According to the legend, during the eighth century the great Tibetan emperor Trisong Detsen held debates between Chinese Buddhists (chan or zen) and Indian Buddhists (Vajrayana) to decide which type of Buddhism the empire was going to adopt as a state religion. Ultimately, the Indian Buddhists won, resulting in Vajrayana influences seen in much of Himalayan art henceforth.

What’s the difference between Zen and Vajrayana Buddhism?

The two traditions differ when it comes to how enlightenment is achieved. Zen strongly emphasizes meditation, and what’s called “spontaneous” enlightenment. By simply meditating as much as possible, a person creates the opportunity for enlightenment to arise within them. Vajrayana, on the other hand, teaches a path of “gradual” enlightenment, providing a prescribed system with the use of many rituals and objects, which is often surprising to many Westerners when comparing Vajrayana to Zen’s minimalist aesthetic. So while many of us love the Rubin’s relaxing atmosphere, think twice before calling it “zen.” You may want to call it “Vajrayana” instead.

Want to experience a true moment of Zen at the Rubin? Learn more about the this tradition at our upcoming screenings of Walk With Me, a documentary that journeys into the world of Zen Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh.

Image Credits:

Buddha Shakyamuni Tibet; 18th century Pigment on cloth Rubin Museum of Art Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin C2006.66.128 (HAR 75);Chakrasamvara in Union with Vajrayogini Central Tibet; 14th century Gilt copper alloy with pigment; Rubin Museum of Art; C2005.16.16 (HAR 65438);Vajra Scepter Vajra Tibet; 16th century metalwork; Rubin Museum of Art; C2004.31.3;Bladdernut Hand Rosary Korea; Early 20th c. Seeds, possibly bladdernut, with image of Bodhidharma carved on each one; Rubin Museum of Art; Gift of Anne Breckenridge Dorsey; C2014.6.13