The following post originally appeared on the International Center of Photography’s website.”‹The International Center of Photography (ICP) is a co-organizer of the Rubin’s latest exhibition, Steve McCurry: India.

Despite the slipperiness of memory, Louise Bourgeois insists that they are her documents and adds, “You have to differentiate between memories. Are you going to them or are they coming to you? If you are going to them, you are wasting time. Nostalgia is not productive.” Documentation is often done to create an archive, a remembrance, but Bourgeois reverses this process choosing to rely on the mutable and the uncertain. The paradoxical place between memory and document is the location of the works in this exhibition.

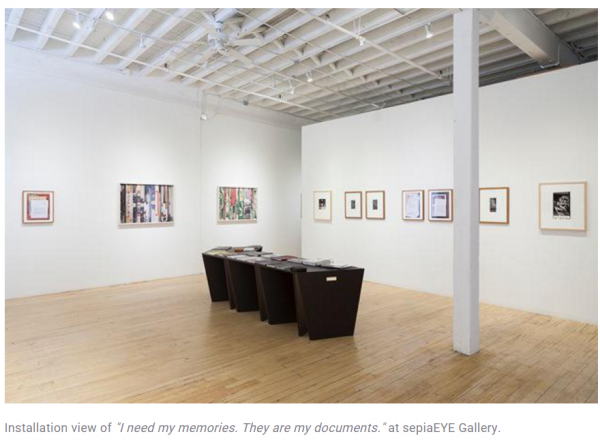

The group exhibition, “I need my memories. They are my documents.” at sepiaEYE Gallery features photographs and videos by five artists who work with a repository of existing visual materials. “I use my fingers, palms, knuckles, and arms to grab, place, hold, nudge, jog, sweep, and shake the different components of the photomontage,” says Pradeep Dalal, explaining the process of creating his photographic collages, Go West. This DJ-like use of disparate materials on the flatbed scanner erects columns of visual slivers that dissolves into one another after a momentary pause. The use of family snapshots, music album covers, textiles, embroidery, prints of palm tress and flowers in the construction of the collages evokes a tactile experience, and reveals how the process of recollection stitches and layers dissonant moments from the past.

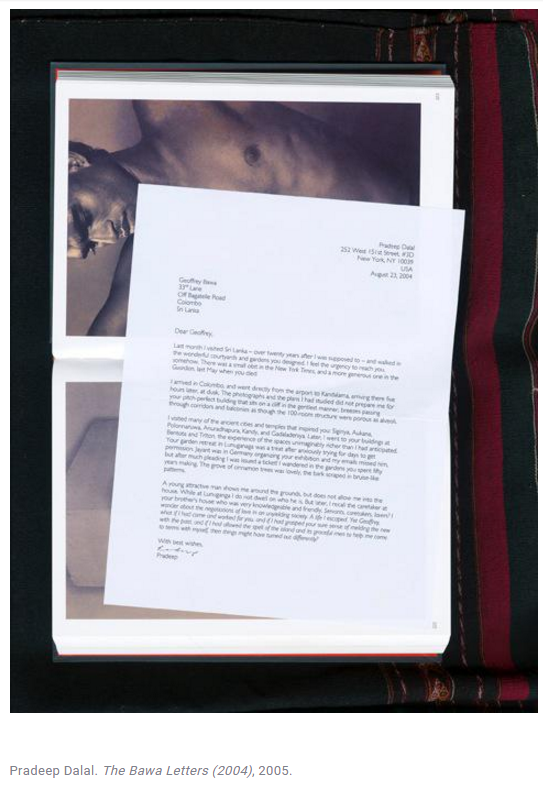

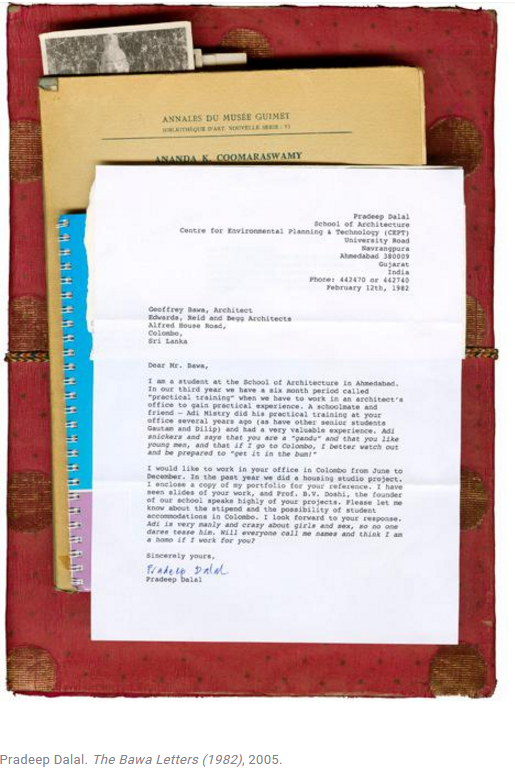

Modernist architecture is a touchstone of Dalal’s work, who received a Master of Architecture degree from MIT after studying the subject in India. The fictional Bawa Letters are written to the Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa known for using regional ideas in contemporary architecture. Using a layered approach, the letters combine background references to Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and Lionel Wendt’s portraiture; thus mingling the pining for vernacular architecture and symbolism with gay desire.

Nandita Raman: Having studied architecture in India and the U.S. and then turning to photography, you must find a wide-open field with multiple perspectives and diverse influences.

Pradeep Dalal: Yes, I feel that there are many, many different approaches in photography and art today. And I am able to take advantage of some of this openness and great freedom to experiment. When I was her student, the artist Kunié Sugiura shared with me her belief that artists who had learned a discipline other than art, had access to material and knowledge that could be useful in expanding the possibilities of photography. I began to find ways to engage more freely with questions and observations I had about architecture and the environment, that I was unable to take on when I practiced as an architect. There are many artists that have opened up new territory, such as Agalia Konrad’s dense and insistent photographic presentation of the exhausted quarries at Carrara, or Hans Eijkelboom’s experiment on a housing project in an Amsterdam suburb, or Abul Kalam Azad’s scarred prints highlighting how ancient monuments are looked after better than ordinary citizens by the Indian government. While I get Lewis Baltz’s point that “photographs are abstractions, their information is selective and incomplete,” I also want art that engages with social concerns and that has a more elastic sense of time—where perhaps the long ago and the present are congruent, closer together.

What is the role of writing or language in your work and thinking? With both writing and visual expression being part of your practice, do you find yourself operating differently when working with the two mediums?

Writing is a way for me to reflect and think through a set of ideas in a more sustained way. I have experimented with different forms of writing such as in the Bawa Letters* and also a transcription of a fictional “˜proceedings from a roundtable’ format in the Lothal project. I realize that when the writing and the art-making work in tandem or at least intertwine in some way then it helps nudge my understanding of a particular set of ideas much further along than is possible by either one alone. I also think that I work with language differently than how I make photographs. While there is a sense of assembly and collage in both, I perhaps need to take more chances with the writing, to be more playful and experimental, wilder even.

How did the Bawa Letters come about?

I cannot recall now how the idea of using the form of letters came about”“I imagine it was just something I may have simply tried and liked. I recall making them quite quickly without too many rounds of trial and error. I made these when I was in the ICP-Bard MFA program over a dozen years ago and showed them as part of my thesis show, but thereafter never had a chance to show them. Thank you for including them in your show—I am pleased to have had friends and others see them.

Your architecture thesis at CEPT University in Ahmedabad was on Le Corbusier’s Assembly building in Chandigarh. How do you now think about vernacular art and architecture alongside Modernist art and architecture?

I deeply identify with many aspects of modern architecture—the functional, no-frills part and some of the modernist work of Charles Correa, B. V. Doshi (especially his CEPT campus where I studied) and Leo Pereira (both of whom were my teachers), which was spare, understated almost austere. But later I was also eager to find a way to see beauty and complexity and sophistication in the traditional and vernacular architecture of India. That has been a slow process and by visiting and photographing many sites of architectural significance in India, I am learning to open up to languages outside of the modernist and western canon. A. K. Ramanujan’s ideas are very helpful. He says: “My interest has always been in the mother tongues, not Sanskrit, because I have always felt that the mother tongues represent a democratic, anti-hierarchic, from-the-ground-up view of India. And my interest in folklore has also been shaped by that. I see in these counter-systems, anti-structures, a protest against official systems.” I am not sure that I see vernacular architecture as a counter system per se, perhaps another way of learning to be open to ingenuity and beauty wherever I can see it, without categories that are restrictive.

The Go West images have such dynamism and knowing that you were moving the materials on the scanner as it was scanning, I wonder if you listened to music while DJ-ing on the scanner?

Probably not, I often have only the radio on when I am working. Still, music is a deep love—a wide range of genres—jazz primarily, and also r&b and blues, and salsa, bachata, and merengue, and a lot of Ethiopian jazz, Congolese rumba—a very wide swath. I have been an avid listener since childhood. I could spend an entire day just listening to music without reading or watching TV or any other distraction—just eyes closed and carefully, attentively listening. Now it is harder to find time to do so.

How did you bring together all the disparate materials used in the collages? Do you find yourself searching and collecting photographs, textiles, books etc. for a possible work?

Not really. I prefer to use things that I live with—woven textiles that are on my couch, chair, or bed; small sacred objects that are on my mantelpiece; books that are on my shelves, old engravings; and 19th century photographs mostly of architecture in India that I enjoy looking at. Also I use Xeroxes of articles that I read on the subway. And I press my own photographs into service too.

You have been teaching in the MFA program at Bard and in many other graduate programs in the city. Does teaching fold into your practice?

I enjoy teaching and have not consciously tried to figure out ways to utilize it into my own way of working. Teaching has encouraged me to become a more careful reader and to articulate my ideas and observations more clearly and assertively. Teaching also makes me more aware of ideas and images I have absorbed, as I am often surprised in studio visits what I can pull out of my mental library. This is especially true at Bard where the interdisciplinary nature of the program really helps me understand that I may have observations and knowledge about sculpture or sound art or poetry or performance that I was not fully aware of. And being around students and faculty who are constantly trying different materials, ideas, techniques is inspirational, and I imagine that this freedom to experiment, slowly feeds back into my own way of working and thinking.

Any artists, writers you are excited about at this time?

I have been working my way through the several collections of superb essays by the artist and educator K. G. Subramanyan. He writes beautifully and with great insight about a range of topics, from how the eye perceives to the uneasy relationship between tradition and modernity. And as he was on the faculty at both Baroda and Santiniketan his deep knowledge about art education and the practice of art in India helps me bridge some of this vast psychological distance that comes from living and working so far away from India.

I am also eager to go and see the Morgan Fisher show at Bortolami in Chelsea. Since this summer I have been reading an elegant and detailed book of his titled Two Exhibitions. In particular, I am really paying attention to a series of works that he developed from the London street atlas. He develops models and procedures to make the paintings not rectangular and the way he thinks of the books as though they were copy photographs is strange and alluring, and he also considers the books thickness and shadow in his compositions. I also just like the broken rectilinear geometry of gray, yellow, and white, and the gray, blue, and white one too. I am also dipping into a companion volume of his writings and another of his conversations (crisp and enviably clear descriptions of his process especially in discussions with other artists—William E. Jones, Frances Stark, and Christopher Williams).

What are you working on currently?

I am just completing a new work—a panoramic image of the bay in Mumbai. I use a 19th-century view of Mumbai as a base and find ways to emphasize the sea and sky over the built landscape of the city. I am getting to work at a larger scale—this print is 9 feet long—which is new for me. And the process itself is also quite different—a more minimal palette and limited set of ingredients or constituent elements, a deliberate attempt to work within a particular set of steps.

And I am also making an artist book called Bhopal, MP, based on the triangulation between architect Charles Correa’s attempt to make a different architecture from the model set by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh— focusing on courtyards and open-air spaces—and the art of Janghar Singh Shyam (a tribal artist) and the Korwas (also tribal artists) and the unique experiment wherein contemporary art, folk art, and tribal art all share space on an equal footing. Here the ideas of the poet and translator A. K. Ramanujan’s idea of counter-systems is grappled with in architecture and modern art and folk and tribal art.

As the Bawa Letters themselves say so much quite directly, I am finding it difficult to say something more about these works. So, I am providing a more tangential path via Coomaraswamy and Wendt—that is something of a backdrop to the letters but help perhaps reveals the large network of ideas and images that are embedded in a work, perhaps as a trace, sometimes not even as a trace but only a sort of ghost-like reference.

*Pradeep Dalal’s text on the Bawa Letters

1. I casually read Herman Hesse as a teenager in Mumbai but it was only many years later that I would realize how attracted I was to the cover of Hesse’s book Siddhartha published by New Directions in 19571. It was a beautiful and somber photograph of a Buddha statue taken by A. K. Coomaraswamy. Later, I found his essay titled “Buddhist Primitives,” which included the full, uncropped photograph. It was captioned: “Buddha in Samadhi,” stone sculpture, Ceylon, 2nd century AD. I traveled to Anuradhapura right after the cease-fire in 2004 when it was forlorn and quiet and I photographed this sculpture, though now it was behind an annoying metal grill and ensconced within an ungainly structure. I found it difficult to square this with the image as Coomaraswamy photographed it, in situ, on the grounds of the Jetavanaramaya stupa.

In his essay, Coomaraswamy explains: “Long before the Buddha image became a cult object, the familiar form of the seated yogi must have presented itself to the Indian mind in inseparable association with the idea of a mental discipline and of the attainment of the highest station of self-oblivion; and when the development of imagery followed there was no other form which could have been made a universally recognized symbol of Him-who-had-thus-attained. This figure of the seated Buddha-yogi, with a far deeper content, is as purely monumental art as that of the Egyptian pyramids; and since it represents the greatest ideal which Indian sculpture ever attempted to express, it is well that we find preserved even a few magnificent examples of comparatively early date. Amongst these the colossal figure at Anuradhapura is almost certainly the best.”2

2. In the late 1990s, my parents went to Sita Eliya the site in Sri Lanka where Sita was held captive by the demon Ravana in the epic Ramayana. They went as a group of pilgrims and believers to a week long reading of Hindu scriptures and invited me to go. I declined almost vehemently, unwilling to go to a religious gathering. After the main event, they traveled to Kandy and especially to the ancient city Polonnaruwa and described their pleasure at seeing the spectacular statues of the Buddha at Gal Vihara. The timeline is hazy, but unwittingly, I was seduced by another New Directions book cover that featured a tender and embraceable portrait of a reclining stone Buddha at Gal Vihara taken by Thomas Merton3. In his journal, Merton describes his encounter: “The path dips down to Gal Vihara: a wide, quiet hollow surrounded with trees. A low outcrop of rock, with a cave cut into it, and beside the cave a big seated Buddha on the left, a reclining Buddha on the right, and Ananda, I guess, standing by the head of the reclining Buddha”¦.I am able to approach the Buddhas barefoot and undisturbed, my feet in wet grass, wet sand. Then the silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing, the peace not of emotional resignation but of Madhyamika, of sunyata, that has seen through every question without trying to discredit anyone or anything—without refutation—without establishing some other argument”¦.Looking at these figures I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things, and an inner clearness, clarity, as if exploding from the rocks themselves, became evident and obvious. The queer evidence of the reclining figure, the smile, the sad smile of Ananda standing with arms folded”¦.” My own experience of photographing the sculptures seems more modest—poignant perhaps but not so revelatory.

3. Lionel Wendt too photographed the Buddha statues at Gal Vihara and other important architectural and archaeological sites in Sri Lanka, but I found his photographs to be overly artful and quite dull. I had chanced on Wendt’s photographs a dozen years ago while browsing through a book on Sri Lankan artists that a friend in Washington, D.C. had received from his father. On my trip I made it a point to go to the Lionel Wendt Art Centre in Colombo and get hold of a copy of a centennial tribute book that contained a large range of Wendt’s photographs including a remarkable set of carefully posed portraits of young men and women that were surprisingly frank and direct. These photographs have a sexual charge that is undiminished even in these supposedly less prudish times. I read somewhere that Wendt knew Geoffrey Bawa, and that they perhaps moved in the same artistic and bohemian circles. However, these portraits seem to be of servants and working class people—rickshaw wallahs, fisherman, singers. A few are named in the catalogue (“Leelawathi” and “Raman”), while most are simply captioned with a placeholder “new addition.” The possibility of social intercourse between the photographer and his subjects is not on the table, yet the closely observed sensuality is daring and unveiled.

References:

1. Hesse, Herman. Siddhartha. New York: New Directions, 1957.

2. “Buddhist Primitives,” in The Dance of Shiva: Fourteen Indian Essays, New York: The Noonday Press, 1957.

3. Burton, Naomi, Hart, Brother Patrick, and Laughlin, The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, New York: New Directions, 1968.

4. Lionel Wendt: A Centennial Tribute, The Lionel Wendt Memorial Fund, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2000