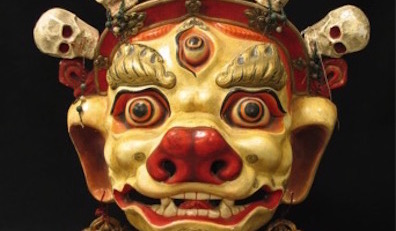

Archaeological finds from around the world show that masks are universal and as old as human history. But masks are not just relics; they are a living form that continues to fascinate us. The beholder of a mask is fascinated by an extraordinary new presence, while the wearer is fascinated by the ability to become someone or something else: an ancestor, an animal, a spirit, a demon, or a fantastic creature. This transformation into another identity can be profound, and in some rituals and shamanistic performances, can even lead to being possessed by spirits. During these ritual activities, masks can imbue the wearer with the qualities and powers of the figure depicted. Masks can also be ambiguous, leaving a tension between the familiar and the strange.

Our recently opened exhibition “Becoming Another: The Power of Masks” juxtaposes masks of the Himalayan region with those from other parts of the Northern Hemisphere, including Mongolia, far eastern Russia, Japan, and the Pacific Northwest Coast of America. These areas were chosen for their vibrant and contrasting mask traditions and cultures that may have been linked through migration in the distant past, if we accept the theory that Asian peoples from long ago crossed the Bering Strait and populated parts of the Americas.

The exhibition presents a great variety of types and styles of masks that are used for a variety of purposes. One type, shamanistic masks, are grouped together to better describe their function in rituals and show the remarkable similarities between the cultures and traditions of peoples from far eastern Russia and those from the Northwest Coast of North America.

Another section of the exhibition presents masks used in communal rituals intended to solidify the well-being of the community, protect it from malicious spirits, assure a good harvest, and consolidate the role of its leaders. A third section focuses on storytelling and theatrical performance. These masks are used in new dramas as well as theatrical reenactments of religious and genealogical myths and legends.

The Himalayan mask examples in the exhibition come from the exceptionally diverse and well-studied collection of Bruce Miller as well as that of the Rubin Museum of Art and include a rich variety of objects from Tibet, Mongolia, Nepal, Bhutan, and the neighboring northern Indian states of Arunachal and Himachal Pradesh. We were lucky enough to collaborate with Eric Chazot, Jean-Christophe Kovacs, and Yvan Kovacs, anthropologists, and experts on the subject, who provided the exhibition descriptions and interpretations of both the Rubin Museum and Miller selections.

The inclusion of masks from the Native tribes of the Pacific Northwest Coast might be unexpected, since they seem, at least geographically and culturally, far away from the Asian groups in the exhibition. However, they have cultural links with the broader Mongolic peoples, particularly in their shamanistic worldview and the ritual implements they use. We are grateful to Barbara Brotherton, Curator of Native American Art at the Seattle Art Museum, who shared with us her extensive knowledge of and long experience with the Pacific Northwest Coast peoples.

Though a diverse array of masks are presented in “Becoming Another,” these fascinating and colorful artworks demonstrate to viewers that people around the world express the same needs and joys in similar ways.