Nepal is known for its impressive religious festivals and traditions—many of which are inspired by the relationship between humans and the natural world. The Museum exhibition Nepalese Seasons: Rain and Ritual invites visitors to explore this relationship through the material culture and ritual celebrations of Nepal.

This past weekend, the awe-inspiring Rato Macchendranath chariot procession began. Every year, Nepalese processioners carry a statue of Macchendranath, the “Red God,” sixteen kilometers from his temple in Patan to another temple in Bungamati. Though the procession occurs annually, the carriage is reconstructed every twelve years, referencing the legendary twelve-year-long drought that Macchendranath brought to an end.

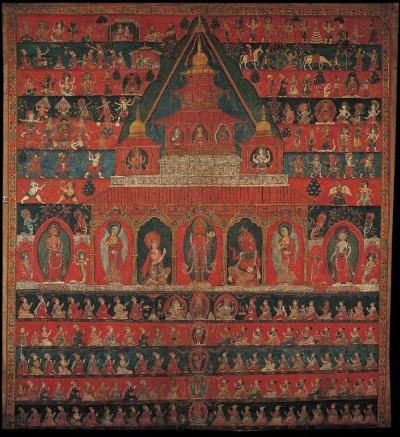

Legend of Rato Macchendranath

Though there are several different versions of this legend, the most popular version involves Rato Macchendranath’s disciple Goraknath: Goraknath, desperate to see his guru, began to pray for his arrival. Unfortunately for the inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley, when Goraknath prayed, he sat on the heads of all the snakes in the valley preventing them from bringing the rains and causing a drought that lasted twelve years.

Eventually, the drought got so bad that representatives from the three major cities of the Kathmandu Valley (the King of Bhaktapur, a Shaman from Kathmandu, and a farmer from Patan) decided that they needed to find Rato Macchendranath no matter what. They eventually discovered that Rato Macchendranath had taken an earthly form and was born to a family of demons in the town of Bungamati. Using his powers, the shaman was able to lead Macchendranath away from the demons and bring him to the center of the valley. Once Macchendranath came, Goraknath stood up to pay tribute to the Red God, freeing the snakes he was sitting on and bringing a return of the rains.

Today, Newars (native people of the Kathmandu Valley) perform the festival before the monsoon begins—around the end of April and beginning of May—to please Rato Macchendranath and ensure the fall of the rains.

Construction of the Chariot

The chariot that carries the sculpture of Rato Machendranath is approximately sixty feet high and weighs around ten tons. Every twelve years, the chariot is made from scratch from carved wood and rope without any nails or screws. Newar priests oversee the construction and perform several rituals and sacrifices to ensure its successful completion. Once the finishing touches are added to the chariot, the sculpture is placed carefully inside and the procession officially begins.

Rato Macchendranath after the Earthquake

In 2015, the procession began on April 22, three days before a devastating earthquake struck the small Himalayan country. After the earthquake hit, Rato Macchendranath’s temple in Bungamati was in ruins, leaving the locals with help from the Nepalese army

searching through the rubble to recover holy items and precious relics. The traditional route had been blocked by rubble as well, forcing the procession to wait until the road was cleared before it could continue. Long after the monsoon rains ended, the procession picked up again in September, completing Rato Macchendranath’s journey and displaying the endurance and faith of the Nepalese people during a time of great hardship.

Discover more connections between Nepalese culture and the monsoon rains at the Rubin Museum exhibition, Nepalese Seasons: Rain and Ritual.