How solitude brings us into a deeper relationship with ourselves

Antonella Lumini is known as a metropolitan hermit. In 1980 at twenty-eight years old an illness changed her life. Finding the reason for her existence became so essential that she began to walk new paths, searching for balance. Her search led her to poustinia, a practice of silence and solitude derived from the Orthodox tradition of eliminating distractions so one can hear the word of God. Antonella lives an ordinary life in her house in the center of Florence that allows for periods of deep silence away and on a daily basis.

Jon Pepper and Patrizia De Libero: The theme for this issue relates to letting go of attachments and seeing things anew. Many of us may like the idea of opening ourselves to a more spiritual life, but at the same time, most people want a comfortable, material life. What is your perspective on this issue?

Antonella Lumini: We are dominated by materialist reason and impulses. This closes our perception and prevents us from investigating our potential—which is linked to our essence and forces from beyond.

I feel it is very important, the conversion of materialistic reason. In this regard quantum physics has been very helpful by demonstrating that an integral part of reality belongs to the invisible realm. So, if we remove the invisible, we cut ourselves off from a possibility and prevent feeling the stimulus to investigate unseen dimensions in life.

But there is a possibility of an underlying awakening because this invisible dimension lives inside human nature. So, from one side, nowadays there is more psychic sickness, as the soul does not find the way towards the light that yearns to reach us. And on the other hand, a vision of life based on materialistic goods and technology makes us more dependent, more attached.

This is a vicious circle. The feeling of lack produces more attachment to the material and our mask—and at the same time puts us in contact with the anguish of seeing there is not a solution in material goods. Only the spiritual dimension can break this attachment and let the mask drop.

Can you speak about the difference between looking for something instead of allowing ourselves to be found?

There are two very important passages in the Bible that speak about the beginning. In Genesis, when God creates the sky and the earth, and in the Gospel of John, the Prologue: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

For me, those passages are important milestones for this theme. They are about an intrinsic movement of the divine. Jewish mysticism speaks about the beginning as an ontological principle. That reminds us “to be”—so the ontologic beginning is something from which the state of being is generated. It is not a temporal principle anymore—but a principle that is always in action. It unfolds itself constantly.

In the Bible the creation is ex nihilo—a creation from nothingness. This passage from nothingness is a great mystery. Therefore, the beginning is the ontological principle that allows the constant passage from nothingness to manifestation.

Being is already manifested. And yet, it is obscure, hidden. The more consciousness expands, the more being manifests and shows itself. Consciousness removes the veil, but the veil needs to be put back, because the light is overwhelming. It can be embraced gradually as consciousness expands.

The act of creation takes us out of nothingness—it takes everything out from the invisible and gives it a form. It is important to understand that this “beginning” constantly renews itself. It is an eternal movement that allows the passage from time to eternity, to live in time but also in eternity.

So human beings, as part of this creation, have to make an effort to see the whole. This is the eschatological way, which means everything will be unveiled to the consciousness of everybody. The beauty of the human being is to see the universal consciousness. Our duty is to be conscious of this universal good in order to take part in this beauty.

Is it possible to change without needing to let go of something?

The central point of all of this is residing in the truth—to perceive what is the emptiness, to enter into the feeling of lack, and move from anguish and attachment to truth in our lives.

While in solitude we are in a deeper relationship with ourselves. This is essential because it gives us the true picture of the inner situation. Stay where you are, stay in the state of being here and now, that is how it begins. This process of descent into oneself unifies us with the process of being, with what we really are.

If we remain in the “mask” we are far away from ourselves, from being able to feel a new sense of being and belonging. We can do many spiritual exercises, but what we miss is the real breaking through. We have to enter in the courage of the truth.

Spirit is light, and truth searches light. Otherwise there is obscurity.

What is really possible for human beings in terms of opening to a different reality, a new way of being in the world?

We have to learn to live the eternity in time and taste things without possessiveness. There is no need to eliminate, deny, or dismiss anything. We have to find a centering point that can give us a right measure from things. Nothing is fundamental, and nothing is to be despised or rejected.

The more we attach, the more we identify with things. If we find our profound identity in the essence in that moment, we can taste everything. We can come to realize that there is nothing to throw away. Everything must be lived in the right way—without attachment. This is the beauty: tasting things with gratitude.

Attachment is produced by a psychic lack or unbalance. The more psyche goes towards the spirit the more attachments drop and what emerges is gratitude and a state of well-being. Then, certain things begin to stop being interesting. Things fall apart on their own, like leaves dropping from the tree. The sense of something lacking has an inscrutable depth. Inside us has been instilled the possibility to feel the lack, but also to fill the lack.

When you enter total emptiness, this lack can be filled with the celestial gift—without dependency. The spirit fills the lack in a peaceful way. But the feeling of lack is what begins everything.

Your practice of poustinia is focused on silence and solitude. What is the relationship between that and being engaged with the world as it relates to opening to a new way to live? Do we need to withdraw?

People ask me, what kind of rules do you have about this? I have only one: the balance between the inner and outer. It is not the isolation itself, going to a top of a mountain and withdrawing, but the state of being. It is living the experience, which means cultivating something inside, giving space inside to something else.

The moment we give space and time to this dimension of silence something opens, and we enter in a different relationship with life and our true essence—getting to know our shadows, our wounds, all of what we are. By seeing and listening to this silent sound, the physical sense becomes spiritualized.

Our essence is just a fragment of the divine essence. Like when we take water from a well—the bucket goes down into the water and takes a part of that whole. In the same way when we go inside of our essence we enter into the divine ocean and touch a part of that. What we understand there is mysterious and seemingly unspeakable. But because it becomes an experience, a sensitive experience, in the end it can be also spoken about.

The divine incarnates in the human and this can be shared. But it cannot be understood or manifested as just a thought. This is why we speak about poustinia “in the square” (in life). Once you withdraw from the world for a time, you come back and can share what has been understood, perceiving and listening to things differently. But unless someone practices in this moment of space and time, the danger is still to live constantly reacting to the world.

Like a plant that has very deep roots, once this practice in solitude is stable there is no need to withdraw all the time. So we always have to have two measures—within ourselves and outside—because this is where we will bring what we have found to use in the world, but not for us alone.

Compassion, mercy, all these qualities—they are like a universal way of perceiving and feeling. But they originate in the deep experience inside oneself, in silence and solitude where suffering rises. Not to escape the world, but to feel the world.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Love is the arrival point. Silence puts you in a state of listening, and through listening one enters a connection with the universal plan.

We have to see ourselves in this divine drawing. Death, evil, darkness—these are just possibilities in life. We do not need to be dominated by this thread. There is something beyond all of this, and we must raise our antenna to connect with what is above this— toward forces that are made of light.

But it is not easy to choose the spiritual way because of the domination of materialistic reasons. So we have to take responsibility and take a commitment to become instruments for something else. The spiritual life is something that begins for healing oneself, but in fact, it has universal consequences. It helps to bring light into the darkness.

About the Contributors

Antonella Lumini has been pursuing a path of silence and solitude for over thirty years. After studying philosophy, she devoted herself to the study of the Bible and texts on Christian spirituality. She worked at the National Central Library of Florence dealing with ancient books. Antonella participates in spirituality meetings and leads meditation groups in Florence and other Italian cities. She has published Inside the Silence (2023) and Deep Memory and Awakening (2008), among other books.

Patrizia De Libero is a native of Rome, Italy, who has studied many spiritual traditions and embraced the Gurdjieff Work since her college days. She runs Kairos Pilgrimages, an organization connecting people to sacred places. Patrizia is a yoga teacher and certified death doula, and she runs the Everything Is Life school of conscious dying and living in North America.

Jon Pepper is a former musician, book designer, and entrepreneur who has almost fifty years of experience with meditation and spiritual pursuit. He is currently a trustee of the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York.

Image Credit

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu is a contemporary master of the Mongol Zurag painting and is widely respected for her innovations in this style. She integrates traditional Mongolian and Buddhist motifs with contemporary themes, as she chronicles the lives of women and everyday, mundane life across the seasons in her post-nomadic homeland. Dagvasambuu graduated from the Institute of Fine Arts, Mongolian University of Arts and Culture. She lives and works in Ulaanbaatar.

A personal story about a radical shift in perspective

Born in Tibet, Chime Dolma grew up in a nomadic herding family, with yaks, dris (female yaks), sheep, goats, and horses under her care. As a young child, she developed a deep connection to the animals. The natural world was her classroom, Mother Nature her teacher. “I spent my childhood on the mountains and had many mountains to myself. I could talk to the mountains and to the rivers. It gave me a deep sense of freedom and liberty.”

Chime loved nature, but when she was in her teens, she watched some of the kids from town walk to school and began to think, “Oh, I wish I could have their life.” Nomadic life gave her the ability to exist in a certain way, but it was also tough on a young person. She had to wake before sunrise and not get to sleep until nine or ten in the evening after a day of physically strenuous work. She never had the opportunity to attend school in Tibet; she first learned to read and write in India, after having to uproot her life and immerse herself in a different cultural, linguistic, and religious environment. “I think my imagination as a child was quite different. I followed that imagination and now live quite the opposite life that I had before.”

After a year in India, she moved with her family to New York, first settling in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, before attending Middlebury College in Vermont. It was a difficult but rewarding journey. “I believe I was drawn to education, and am an educator today, because of my deep connection to the Tibetan community,” Chime says. In graduate school, this connection to her Tibetan heritage made her question her place in the world because she felt a huge responsibility to do something about the plight of Tibetans. At the same time, she read books that discussed the danger of having a single story and clinging to one particular identity. These concurrent ideas propelled Chime “to think deeply about who I am and what it means to be part of a shared humanity.” She dedicated herself to helping Tibetans who are struggling or don’t have the same access to educational opportunities or even health care that she had.

Chime doesn’t have all the answers yet, but community and identity are ideas she continues to explore as she asks herself, “How can I best serve a larger purpose in the world?”

About the Contributors

Chime Dolma is the cofounder and president of YindaYin Coaching, a nonprofit organization that primarily serves immigrant communities in New York by focusing on community empowerment, education, and mentorship. She is an educator and currently works as the director of global studies and a history teacher at Riverdale Country School. Chime also serves on the advisory council of the Rubin Museum.

Howard Kaplan is an editor and writer who helped found Spiral magazine in 2017. He currently works at the Smithsonian and divides his time between Washington, DC, and New York City.

Image Credit

IMAGINE (a.k.a. Sneha Shrestha) is a Nepali artist who incorporates her native language and the aesthetics of Sanskrit scriptures into her work. Her art has been featured in several exhibitions, and her public walls appear across the world from Kathmandu to Boston. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, recently acquired her painting Home416, making her the first contemporary Nepali artist to be part of the museum’s collection. Sneha received her master’s from Harvard University.

Attachment theory through the lens of social neuroscience

“The propensity to make strong emotional bonds to particular individuals is a basic component of human nature.” —John Bowlby

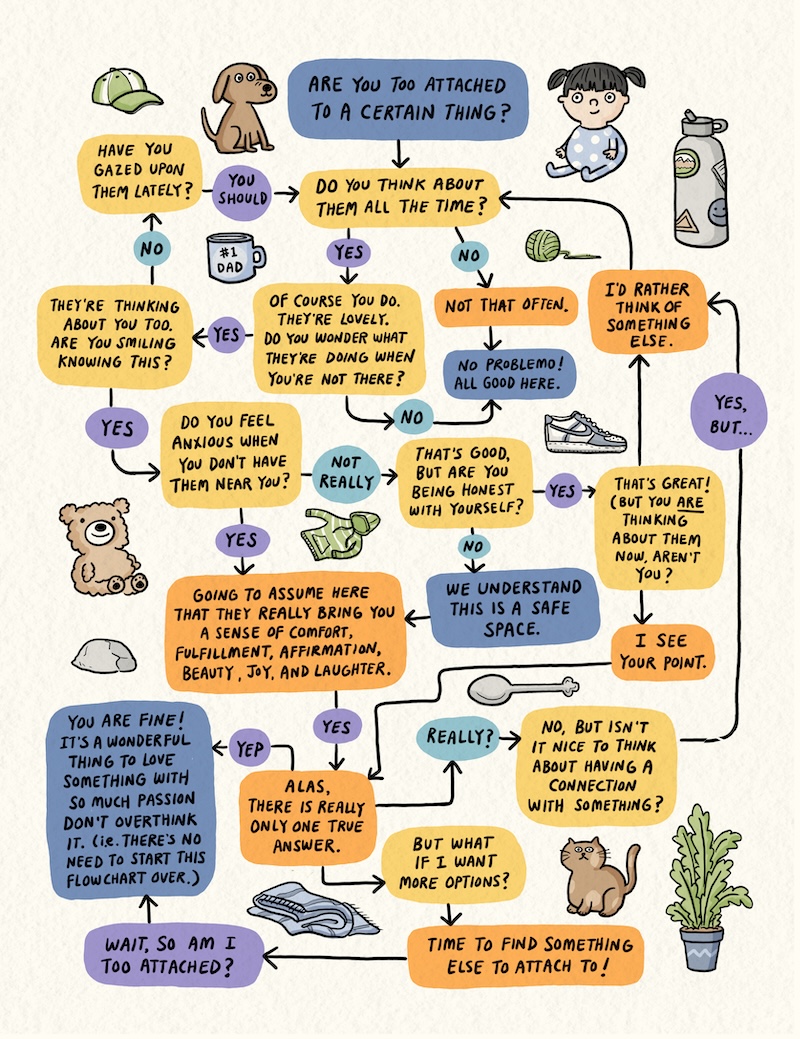

Attachment is a word that seems to be on everyone’s lips these days, especially on social media, where it comes up in association with relationships, parenting, mental health, and more. As a social neuroscientist who has studied human attachment for almost two decades, I notice how the discussions online, encompassing a wide range of perspectives, often result in disagreement and confusion. I also see how exploring attachment through the combined lenses of psychology and social neuroscience offers a clarifying and unifying path forward. Such a framework helps to unravel the neuropsychological basis of our fundamental social nature.

Attachment Theory

Human infants, as compared to other mammals, are born early and helpless. They cannot survive without constant, intensive care. Put differently, infants strongly rely on external coregulation—help from others to maintain physical and mental balance (homeostasis) and to successfully predict and respond to constantly changing environmental demands (allostasis). What is more, infants’ dependence on social closeness and protection lasts much longer than in other mammals due to a vastly prolonged developmental period. Evolution has therefore equipped infants with sophisticated social survival tools. These tools function to ensure that infants can signal when they need support and that their signals reliably elicit an immediate and appropriate caregiving response.

Starting in the 1950s, John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth were the first to recognize and systematically explore the above mechanisms by developing attachment theory. At the core of their research and theorizing was the realization that—because all infants need to develop strong, enduring emotional bonds to significant others for survival—it is not the presence versus absence or the “strength” of attachment that is most important. What counts above all is the quality of the infant-caregiver attachment and how it varies between different infant-caregiver pairs.

Another key ingredient of attachment theory is the notion that infants will start forming expectations and predictions about future social interactions based on past interactions with their caregivers. Here, two aspects are of particular importance: how much effort it takes to elicit a caregiving response and how efficient the caregiving response is in alleviating distress. Accordingly, a high-quality infant-caregiver interaction requires little effort from the infant to elicit care and is very effective in helping the infant with allostasis and thereby restoring homeostasis. That is why support seeking under distress is deemed the primary attachment strategy associated with a secure attachment pattern. Finally, attachment theory assumes that the above considerations can be extended from infants to children, adolescents, and adults, as the need for coregulation under distress remains a prominent hallmark of our species across the entire lifespan.

How Does Social Neuroscience Fit In?

Social neuroscience is the study of the neurobiology underlying human social behavior. It can shed light on the neuropsychological basis of our strong dependence on social closeness and care to maintain homeostasis and perform allostasis. There is growing evidence that our brain treats our own resources and the resources provided by others almost interchangeably. The less we have to worry and the more helping hands—literally as well as figuratively speaking—we have available when we are in need, the more energy we can conserve. We can then use this energy for other activities like exploration, learning, and self-care. It therefore makes perfect sense to ensure close social connection to others and seek their help and support when facing a challenge.

Social neuroscience can also help explain what happens if our social resources are reduced or when it becomes difficult for us to reliably predict their availability under distress—in other words, if our primary attachment strategy associated with secure attachment becomes increasingly futile and inefficient. Because we are still in need of coregulation to perform allostasis, we must come up with compensation strategies.

One strategy, called “individual fight,” aims at increasing our own physical and mental resources to face challenges independently. If nobody is there to help us, we need to fend for ourselves. In attachment terms, we start employing a secondary attachment strategy related to avoidance and attachment system deactivation. Another strategy, “social flight,” aims at socially reconnecting to others by increasing our support-seeking attempts and thus the chances of our cries for help being heard. In attachment terms, we employ a secondary attachment strategy linked to anxiety and attachment system hyperactivation.

Crucially, both avoidant and anxious secondary attachment strategies are meaningful and often necessary as they represent adaptive responses to specific environmental demands. And they usually work quite efficiently, especially to resolve short-term increased allostatic demands under moderate distress. We should therefore not regard these two insecure attachment strategies as bad or dysfunctional as such. That said, prolonged or intensive use of compensation strategies inevitably leads to wear and tear and thus constitutes a prominent risk factor for the emergence of physical and mental health issues.

Social neuroscience can also illustrate what happens if we experience a complete lack of social resources or if they become a threat by themselves. This usually happens when we face prolonged adversity associated with a diverse range of socioeconomic stressors (including poverty, parental mental health issues or substance abuse, etc.) or repeated experiences of neglect or maltreatment. It yields what we call “tertiary disorganized strategies” with two main neurobiological fingerprints.

On the one hand, prolonged unavailability of others for coregulation and allostasis will give rise to a pattern of hypo-arousal and emotional blunting, because the cost of constant, intensive self-regulation eventually becomes unsustainable. On the other hand, repeated maltreatment will result in a pattern of hyper-arousal characterized by increased emotional sensitivity. We link this pattern with an often-observed approach-avoidance conflict due to the maltreating caregivers’ dual role of providing both care and being a source of threat. Since these tertiary disorganized strategies are much more rigid and extreme, they also bear a much larger potential for allostatic overload and ensuing physical and mental health issues.

A Unifying Framework

How then can a combined psychology and social neuroscience framework help to resolve confusion and unify perspectives on attachment? I believe the crucial element is the addition of objective neurobiological data. If a consistent neurobiological pattern emerges across studies that employed different attachment measures, the overlapping social neuroscience component can help find common denominators. This will also clarify definitions and technical meanings of attachment terms that vary considerably depending on the psychology tradition and research method they were initially derived from.

We can also compare objective neurobiological data pertaining to attachment with corresponding findings from other social neuroscience domains and check for overlaps. For example, the above-delineated framework draws on Social Baseline Theory as well as other considerations associated with the neurobiological basis of social, emotional, and cognitive information processing and social allostasis. Such comparisons show that attachment shares many properties with other vital neuropsychological functions and that research and theory pertaining to these other functions can fruitfully inform and extend our knowledge about attachment.

We still have a lot to learn about attachment. But taking a combined psychology and social neuroscience perspective offers many pathways to better understand ourselves as individuals and as a species that is ultimately reliant on one another.

References

Long, M., Verbeke, W., Ein-Dor, T., and Vrtička, P. “A Functional Neuro-Anatomical Model of Human Attachment (NAMA): Insights from First- and Second-Person Social Neuroscience.” Cortex 126 (2020): 281–321.

White, L. O. et al. “Conceptual Analysis: A Social Neuroscience Approach to Interpersonal Interaction in the Context of Disruption and Disorganization of Attachment (NAMDA).” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (2020).

White, L., Kungl, M., and Vrtička, P. “Charting the Social Neuroscience of Human Attachment (SoNeAt).” Attachment and Human Development 25 (2023): 1–18.

About the Contributor

Dr. Pascal Vrtička is an associate professor and principal investigator of the Social Neuroscience of Human Attachment (SoNeAt) Lab at the University of Essex in Colchester, United Kingdom. In addition, he acts as coordinating board president of the special interest research group Social Neuroscience of Human Attachment (SIRG SoNeAt) situated within the Society for Emotion and Attachment Studies (SEAS), where he also is an associate member of the executive board. Learn more about his work at pvrticka.com.

Image Credit

Anuj Shrestha is an illustrator and cartoonist currently living in Philadelphia, PA. His illustration work has appeared in the New York Times, New Yorker, Washington Post, ProPublica, and Playboy, among others. His comics have received gold medals from The Society of Illustrators. He is fond of Italian horror movies, dumplings with chili oil, and chihuahuas.

Finding inspiration in community and daily life

Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now presents artworks by thirty-two contemporary artists, many from the Himalayan region and diaspora, juxtaposed with objects from the Rubin Museum’s collection. Co-curator Tsewang Lhamo interviewed artist Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee about his process creating a new work for this exhibition.

Tsewang Lhamo: What is your work in Reimagine about? What does it mean to you, and why is it important for you?

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee: My works are important to me because of their subjects. Most of the time, I choose my family, my friends, and people I deal with on a daily basis as the main subjects.

For this show, I chose the local bus stand in New Delhi because I’ve been using that space for a very long time. This bus stand has become kind of my family in a way. So the characters in the painting, along with the materials, all come from my experience being on the bus.

There are lots of people here in this artwork, and it reflects the fact that India is the most populated country in the world. Delhi is one of the most dense cities in India. When I go to the bus station in the morning, which is the busiest time of day, people do not fit in the bus. So in the painting, there are characters that come out from the bus, sort of like a tower going up in the sky.

Some of the characters shown are Indian circus performers, musicians in bands who play instruments during marriage seasons, and sex workers, who are commonly seen at bus stations in India.

What this particular work means to me is that despite having your own country, culture, and religion, without understanding each other on a humanity level, I think we all are lonely and narrow-minded. Our differences shouldn’t act like a cage.

What is your preferred medium? What materials did you use to create this piece, and is there any significance in those materials?

I normally paint with acrylic on a tarp. We call it drochak bureh (drochak means barley and bureh means sack). This material is important for me because when we were kids you could see these bags everywhere in our towns on broken windows to cover them, during construction, as garbage cans, and some people even made bath loofahs out of them. During college, canvas was so expensive for me, so I began to use this material.

I remember drochak bureh when I was a kid in India too. It’s a nostalgic piece of material for us. Can you share a little history about how they got to the Tibetan settlements in India?

I see it as a symbol of our refugee situation. My parents would say, “We are refugees. That’s why we are getting this.” The bags were filled with food supplies as aid, and they were given by the United States to Tibetan refugees back then. The ones you see now are quite different from the ones from back then, especially the ones in Delhi. But they also carry its role in a different way, used for different things.

What sacred objects from the Rubin Museum collection did you choose to engage with in your work and why?

I’m playing with three objects from the collection: the Monkey Mask, the Kang Ling leg bone trumpet, and the Garland Bearing Apsara wooden carving that the Rubin recently returned to Nepal I saw it in the newspaper and thought it was very brave of the Rubin Museum to give it back to Nepal, so you can see its return in my work as well.

I use the Monkey Mask for my character because of Hanuman, who is very loyal to Ram. I want to show my loyalty to the Indian community, like Hanuman does to Ram. Indians are very kind to us. On top of that I use the Tibetan mask, which represents me. With the Kang Ling trumpet, it is a juxtaposition with the Indian band Baja instruments. The Kang Ling reminds us of emptiness and impermanence, and the band Baja is kind of materialistic and represents attachment, because it’s usually present in marriage ceremonies in India.

All stolen sacred cultural artifacts have the right to return. They are the ancestral kin of indigenous people from the places they came from. The return of the Apsara included in your work shows me what the future holds. May we see all of them returned in this lifetime.

How do you reframe your perspective when you feel stuck while creating art?

I normally stop and try to find humor in my work, and then I call my friends and talk about it. It somehow changes the way I see my work when I joke about it with my friends. From there, I am able to create new paths. Even my father says, when you are going through great misery or you are stuck somewhere, you should realize that there’s always humor in it. I hope my paintings can bring humor into peoples’ lives. Making a full painting and letting it go by selling it and then making another one—that is part of the process for me.

What brings you peace and joy?

Love. Without love there is no joy as a being. It makes you lonely. That’s the special thing about humans. We can love each other without any kind of boundaries about our culture and everything else.

What future or collaborations do you envision for our art community?

Because of technology, I can see what other artists are doing and what galleries are showing new works. It helps a lot when seeking inspiration. Because we are able to communicate so easily now due to technology, it will be better for our art community, and art can better technology and community too.

When I was in school, I never liked to collaborate with people. I found it a disturbance when I needed personal space. I think in other places, even when you collaborate, there is still some personal space. But in India we don’t have any personal space.

Someday in the future, I want to collaborate with my senior artists. That inspiration came from Andy Warhol and Jean Michel Basquiat when they collaborated.

See these artworks in the exhibition Reimagine: Himalayan Art Now on view at the Rubin Museum from March 15 to October 6, 2024.

About the Contributors

Tenzin Gyurmey Dorjee was born in 1987 in Kamrao Village, Himachal Pradesh, India. He is interested in exploring the paradoxes present in ordinary things and how global changes in culture, politics, climate, and science can impact local surroundings. His father, Tulku Troegyal, taught him drawing in the Tibetan traditional style at the age of six, and he has been practicing arts professionally since 2013. His studio practice is currently based in Delhi. www.tenzingyurmeydorjee.com

Tsewang Lhamo, also known as Tselha (they/ཁོང་), is a queer Tibetan multidisciplinary artist, self-taught filmmaker, and cultural producer based in Queens, New York. Born in Nepal, they grew up in a Tibetan refugee settlement in South India. Previously a graphic/web designer, they founded the Yakpo Collective, a Tibetan contemporary art platform centering Tibetan creatives around the world. They are also one of the organizing members of Tibetan Equality Project, a space dedicated to the queer Tibetan community in diaspora. In the future, they plan to create feature-length queer Tibetan films. www.tselha.com

A personal story about a radical shift in perspective

In the fall of 2004, Arun Ayyagari was scheduled to attend a technical workshop in Nuremberg, Germany. The flight missed its scheduled takeoff from Newcastle, England, and kept getting delayed. Rather than arriving early in the evening, he landed in Germany after midnight when the hotel front desk had closed for the night. After a taxi dropped him off, he stood on the empty street, ringing the bell. But as the minutes passed it seemed unlikely anyone was coming to let him inside.

When Arun turned around, he noticed the taxi was still at the curb, the driver craning his head to see what was happening. “Everything was closed. I was tired, hungry,” he said, adding, “language was a problem, although there was nobody on the streets to talk to.” The driver found a restaurant that was about to close: the lights were dimming, the neon sign just turned off. But when Arun opened the door and explained his situation, the owner prepared some food for him and even refused to take any money.

The restaurant owner asked where Arun was staying for the night. Arun told him that the hotel front desk was closed. The owner didn’t hesitate in telling him that he would arrange a place for him to stay. Arun politely refused and said he couldn’t accept the offer. But the restaurant owner insisted and then drove Arun to a nearby friend’s house where he woke the friend up. “Everything was so surreal that I was beyond grateful. After having my breakfast in the morning, I naively asked this gentleman why he trusted me, and he replied, ‘We are all human and should help each other.’” For Arun, that became what he refers to as a “lightbulb moment.”

That transformational conversation forever changed his thinking. Ever since, he has been someone who consciously helps others. “Stranger or acquaintance, near or dear, needy or not, it does not matter to me,” he says. This encounter helped Arun realize that self-actualization can come from actions big and small, including helping individuals, communities, or any cause that can leave an indelible impact on other people’s lives.

This new way of thinking led Arun to become involved in leadership roles in nonprofit organizations like Lead Foundation Global, where as president he champions youth initiatives and cultivates leadership skills. He does this by collaborating with the United Nations and other like-minded organizations in focusing on sustainable development goals, particularly quality education and clean water.

Those twenty-four hours in Germany helped him redefine what it means to be a citizen of the world and to expand on the definition of the word help. “Life, I’ve come to understand,” Arun adds, “is the best dictionary.”

About the Contributors

Arun Ayyagari is an editor and policy analyst who writes on foreign policy, geopolitics, and international relations. He is a fellow at American Indo-Pacific Forum, a think tank in Washington, DC. He is an advanced pilot, commercial pilot, and drone pilot, and teaches US history, social studies, rocket science, and aerospace engineering.

Howard Kaplan is an editor and writer who helped found Spiral magazine in 2017. He currently works at the Smithsonian and divides his time between Washington, DC, and New York City.

Image Credit

IMAGINE (a.k.a. Sneha Shrestha) is a Nepali artist who incorporates her native language and the aesthetics of Sanskrit scriptures into her work. Her art has been featured in several exhibitions, and her public walls appear across the world from Kathmandu to Boston. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, recently acquired her painting Home416, making her the first contemporary Nepali artist to be part of the museum’s collection. Sneha received her master’s from Harvard University.

Overcoming attachment through focus on mastering bliss

As explained in Tibetan commentaries, practices focused on the tantric deity Chakrasamvara and his consort Vajrayogini are means of overcoming attachment, desire, and the ignorance of not realizing the true nature of reality, which is the emptiness of all phenomena. These mental afflictions are among the fundamental causes of the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth known as samsara. The central deities in this painting are in sexual embrace, a symbolic representation of secret tantric teachings on the union of wisdom and method necessary for achieving full awakening. In tantra, this state of awareness is also known as the supreme bliss.

The name Chakrasamvara in Sanskrit means Circle (chakra) of Gathered Together Deities (samvara) in reference to the deities representing all aspects of body, speech, and mind required for a practitioner’s nonconceptual realization of emptiness through experiences of subtle bliss. Tibetan translations of the name clarify its meaning, emphasizing bliss and pleasure and forming the name Demchok (bde mchog), meaning Supreme Bliss.

Chakrasamvara practices are meant for the initiated to help cultivate and experience the stages of bliss that enable them to attain the subtlest level of mind, or pure awareness known as the clear light. With this awareness they are able to gain insight into the meaning of emptiness and eventually become a buddha.

This painting’s well-recorded composition presents a group of deities that are neither part of the mandala of Chakrasamvara nor belong to the same practice, but they are loosely grouped as they all relate to practices for extending life. Prolonging lifespan is not the ultimate objective of long-life practices, but it is considered a helpful condition that allows more time to work toward the goal of awakening.

See this painting in the exhibition Masterworks: A Journey through Himalayan Art at the Rubin Museum of Art through October 6, 2024.

About the Contributor

Elena Pakhoutova is a senior curator of Himalayan art at the Rubin Museum of Art and holds a PhD in Asian art history from the University of Virginia. She has curated several exhibitions at the Rubin, most recently Death Is Not the End (2023), The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel (2019), and The Second Buddha: Master of Time (2018).

Image Credit

White Chakrasamvara with Consort, and Six Deities; from The Twenty-seven Tantric Deities series designed and commissioned by Situ Panchen (1700–1774) from Tsewang Drakpa of Jeto; Kham region, eastern Tibet; ca. 18th century; pigments on cloth; Rubin Museum of Art; C2006.66.15 (HAR 432)

About the Contributor

Ruth Chan is an illustrator and author who spent her childhood tobogganing in Canada, her teens in China, a number of years studying art and education, and a decade working with youth and families in underserved communities. She now writes and illustrates full-time in Brooklyn, NY. Visit ohtruth.com for more info.

Harnessing the wisdom of emptiness to generate compassion

Khandro Kunga Bumma, known as Khandro-la affectionately by her followers around the world, left Tibet after having a series of visions to lead a spiritual life. Following her arrival in Nepal and with great hardship, including Khandro Kunga Bumma, known as Khandro-la affectionately by her followers around the world, left Tibet after having a series of visions to lead a spiritual life. Following her arrival in Nepal and with great hardship, including extreme health challenges, she went to India to meet with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. His Holiness recognized Khandro-la as a realized practitioner and the State Medium of the Tenma Oracle. He gave her the title Rangjung Neljorma, “Self-Arisen Dakini.”

Tenzin Gelek: How do you describe non-attachment?

Khandro-la: In Buddhist teaching, when we refer to attachment, we are talking about an affliction that obscures our mind. Our mind is obscured by ignorance, the misconception about how things exist and the belief that things exist independently without any causes and conditions. This wrong view propels attachment and other afflictions. We believe that attachment, by nature, is incidental, temporary, and interdependent. When we separate it from our mind with proper application of causes and conditions such as wisdom and methods, we can remove attachment from our mind, and we can achieve a state of non-attachment. Therefore, sometimes we use the term non-attachment as a means to describe our true nature of mind, which is devoid of attachment and other afflictions. Our true nature of mind is clear, illuminating, and empty.

Is compassion a form of attachment?

When we experience compassion, loving kindness, and bodhicitta, or awakening mind, we get attachment to sentient beings, such as to our family members. Although it is a form of attachment, there is a difference, depending how you feel the attachment and the causes for such an attachment. Attachment driven by compassion, love, and bodhicitta is not strictly affliction. This is because we can experience these feelings such as compassion without the self-grasping mind or seeing them as intrinsic.

Is non-attachment the same as detachment?

Non-attachment can be used to describe people who realize emptiness directly. When you look at the true nature of mind, it is free of attachment, so it can be both the state of non-attachment and detachment. But when we are in meditative equipoise, single pointedly placing our mind to an object, we do not experience the gross level of attachment. However, our mind is not totally free of attachment as we have not realized emptiness yet.

So to attain a non-attachment state you need to realize emptiness?

Yes. Only when we have realized emptiness are we in the state of non-attachment. In other words, when we have not realized emptiness, we are still under the influence of attachment, although sometimes the attachment is not active.

Is attachment a bad thing? What about being attached to loved ones?

There are different ways to practice our compassion to sentient beings. For example, when people show their compassion to someone who is lacking a means of living or survival, they do so by perceiving that the person exists intrinsically, that is independently without any causes and conditions. Likewise, their compassion, and the practitioner themself, all of these different parts are viewed as though everything has an intrinsic nature. This is what most of us do. This type of perception reinforces our confusion or ignorance and creates further afflictive emotions such as attachment and anger that produce pain.

We can view all sentient beings and their circumstances, our existence and practices, as a product of dependent origination and lacking intrinsic nature—everything we see as labeled by our mind or a projection of our mind. We come to understand that all of these phenomena are interdependent, yet they are fully functioning in conventional reality, so they experience favorable and non-favorable conditions through the workings of dependent origination. This type of view of compassion is proper and considered very powerful.

From this perspective, we see that although everything is lacking intrinsic nature, other sentient beings are still under the influence of the self-grasping mind and ignorance. They hold self as intrinsic, and through this misperception about self, they get attached to it and other things. This propels jealousy, harmful thoughts, perverted views, all sorts of suffering. This leads to conflict among family and nations.

With this understanding we feel compassion and love to sentient beings and wish them to be free of suffering. There is a sort of attachment here, but it is not propelled by ignorance. It is not an attachment that propels suffering. This can be a pure attachment, a sense of virtuous emotion, and it is not an attachment strictly defined in our ordinary sense.

We feel love for our family members, parents, and children. In an ordinary sense, it is a positive feeling. But it is still a form of attachment. These loves formed by seeing things as intrinsic nature become causes for sufferings later.

Can you share an example?

When a couple first gets married, their attachment to each other provides pleasure. However, this pleasure does not exist intrinsically and doesn’t last. When you are attached to a person, you don’t see the person is composed of flesh, bones, and other substances that are conditional and subject to decay. You don’t see the person is under the influence of afflictions such as attachment and anger.

When we get attached to such a person, we see the person as incredibly beautiful, the best, the most precious, and totally solid and permanent. However, when we observe carefully, in reality, we realize that they are constantly changing, subject to impermanence and the conditions and causes that produce suffering. We also realize that this attachment itself is a source of suffering for them and for us.

Our attachment to them provides benefit in the short term, physically and mentally. We later realize that our perception of them is incorrect, and we are holding the wrong view of the person. This is because we confuse the impermanent as the permanent, the nature of suffering as the happiness, the impure nature as the pure nature, selfless nature as self-nature.

Of course, we need a companion, income, a good reputation—there’s nothing wrong with that. However, we must realize that these are produced with causes and conditions, and they lack intrinsic nature.

How can we practice non-attachment to materials and people that are not healthy?

In order to confront this issue, we must realize that we are confused. So we should not look outside but look introspectively, inside our mind. We should examine the true nature of the object of our attachment, the true nature of our mind that gets attached to it. We need to examine what the mind looks like when we feel attached, how this mind grasps things, what is the aim or what does the mind want, what is the result of this attachment. First we ask these questions to ourselves. Then we can focus our examination to the object of our attachment by looking at how we perceive that object or person.

For example, when we don’t like someone, rather than trying to change the person, we need to look at our perception, observe and investigate how this dislike feeling is taking shape in our mind. We will realize that, in most cases, this disliking has more to do with ourselves, our ignorance or confused state of our mind, rather than how things exist out there. This method is a good approach for dealing with our attachment to the wrong things. If we don’t change our mind or attitude by looking introspectively, we can’t change our behavior.

Is practicing non-attachment a realistic goal?

Yes. When we talk about happiness and suffering, they are not permanent and intrinsic. They are interdependent and relative, so they can be changed and abandoned. Attachment is a form of an ignorant state of our mind; this ignorance is incidental and temporary but not the true nature of our mind. The true nature of our mind is pure, clear, bright, and empty. Attachment and other afflictions are circumstantial and incidental; they are formed through interdependent and relative conditions. To dismantle the attachment, we need to look at the reality of the attachment and how the attachment is formed. If we are able to understand that materials and people do not exist as we perceive them to, then our attachment will fall apart.

In order to dismantle suffering, we need to dismantle attachment. Therefore, relying on the wisdom of emptiness to dismantle attachment is the most powerful tool. Not only does it enable us to root out attachment but it also enables us to generate a powerful compassion and loving-kindness that we can extend to all beings. Through seeing the true nature of all things, seeing that everything is part of dependent origination, we are able to abandon our attachment to a select group of people. We see every being as the same in their basic nature and conditions, thus enabling us to see and extend our compassion and loving-kindness to all.

How can we practice non-attachment in daily life?

First we need to see the negative results of attachment. Then there are many approaches we can use to abandon attachment, including understanding the true nature of attachment—that everything lacks intrinsic nature and that attachment itself is impermanent and interdependent. Then there are practical means to reduce attachment, including being aware of thoughts that reinforce it.

How can we be goal oriented while practicing non-attachment?

When we think about our goals, we need to understand that we do not want suffering and our ultimate goal is happiness. Likewise, all other sentient beings wish for the same thing. So our intention or motivation should not be only focused on oneself but for all sentient beings, as we are all connected.

Since all phenomena are relative and dependent on each other, we know that they are not absolute and inherent. If we follow such a view, then practicing the Buddhist Dharma and doing business are not two separate things. The clearer we see the workings of interdependence and interconnection the less conflict we see between achieving goals and practicing non-attachment. When we are not attached and have a pure intention, it helps open our hearts to accomplish many things.

How does one handle the paradox of being attached to practicing non-attachment?

A temporary way of letting go of attachment is practicing a single-pointed concentration meditation technique. Although it pacifies our gross level of attachment in the short term, it does not totally abandon our attachment. When we come out of our meditation or yoga, the afflictions such as attachment and anger will appear again.

In order to abandon attachment effectively, we have to work with the root causes of attachment, which is getting rid of self-grasping and self-cherishing minds. If our practice does not deal with these two elements, our abandonment becomes shallow. You can press down the attachment, but it will appear again when opportunities arise.

Therefore, if we are getting attached to our non-attachment practice, we need to become familiar with the correct understanding of our mind and our attachments. Through continuous practices, we will be able to overcome any form of attachment.

How is non-attachment related to freedom and liberation or enlightenment?

Buddhists believe that knowing the true nature of the mind and becoming familiar with it will root out all sources of affliction including attachment. Once we attain this realization, our mind is free of all affliction, devoid of attachment, and embedded with all good qualities. This level where the true nature of our mind is realized is what we call Sanggye, or Enlightenment. It is a state of mind rather than a destination or a place.

What role does it play in identity formation?

When we say for example, “I am an American,” I am this and that, and so on, the very concept about “I” is a form of attachment. Here one is holding the concept about “I” as intrinsic and absolute. When our mind is bound by this concept of a concrete “I”, it becomes attachment, and it naturally becomes confused.

Whenever we see forms, hear sounds, taste things, and feel emotions, our attachment become activated. The attachment goes hand in hand with the grasping mind, with craving. So we are not saying that everything that we attach to is empty. Speaking relatively, we can enjoy good qualities and things. We should not say this is a form of attachment and we should abandon it. But we should not be attached to the concept of them existing intrinsically. Once we understand the true nature of how things exist, it opens our mind, enabling us to practice loving-kindness and compassion to all beings.

About the Contributors

Khandro-la teaches around the world and is a sought-after speaker for her wisdom and compassion. Her teachings focus on generating bodhicitta, the awakened mind, and the wisdom of emptiness. She also serves as an advisor to numerous Buddhist teachers and their Dharma centers globally.

Tenzin Gelek is senior specialist, Himalayan arts and culture, at the Rubin Museum of Art.

On surrender and awakening

Sonya Renee Taylor and adrienne maree brown have been collaborators since 2017 when adrienne interviewed Sonya for her book Pleasure Activism. In 2020 they did an event that became the spark for not only their friendship but also the cocreation of The Institute of Radical Permission and Journal of Radical Permission. Here the two authors and activists talk about how Sonya came to a radically new orientation towards herself and her perspective on life.

adrienne maree brown: Who would you say that you were socialized and conditioned to be?

Sonya Renee Taylor: I was socialized and conditioned to caretake, but in a particular kind of way, like to crisis caretake. I was conditioned around parentification as a child of an addict. A lot of survival responsibilities fell on me.

And then as I got older, I was socialized to operate with a certain level of extraction, like you need to figure out how to have your needs met, and here are some strategies. Here’s the strategy of desirability. Here’s the strategy of smartness. Here’s the strategy of hustler. These are all roles that I played as a way to extract what I needed from wherever it was locked.

Do you remember your first awakening experience that made you question that conditioning?

In 2020, the great collapse was happening both societally and in my personal life. My partner and I had broken up. My dog had terminal cancer and was about to die. I was in a country that had just gone on a complete lockdown, and I was living alone in this house that was supposed to be a place where I was going to be doing healing retreats. There was this wave of despair that came rushing toward me. I had this sense that if I did not employ whatever exists beyond me I was going to be consumed by this despair.

There was a drum in my house from a friend of mine. I got the drum, and I started chanting and playing the drum, like rebuking that wave of despair. It was the first time where I was like, Oh, I’m an invocation of all of the entities that assist me. I am at the point where I need all of the energies, all of the tools, all of the resources to make it through this experience. That was the first time it felt like there is something opening in me that knows that I cannot do this alone.

There’s the way that we orient towards getting through something hard. And then there’s the way that we orient towards awakening. What for you was the moment of choosing then to begin to move towards awakening in your life?

There were two moments of surrender. The first was not long after the invocation of all the energies and spirits to assist me. I was in the shower, and again, I was just like, this is the most painful thing. When is this over? Whatever “this” is I’m in. When is this over? I had been listening to gospel songs, and it was as if on cue this song played that goes, “It ain’t over until God says it’s over.” I literally shower slid down the wall weeping, and I was just like, fine. I surrender. Clearly, I’m out of my field of control, and there’s nothing you can do except to surrender to it.

I feel like I surrendered, but it was a resistant surrender, as for a long time I experienced it like a punishment. I felt life is stripping me of everything, cause life hates me, cause I’ve been bad, cause I didn’t get it right. I could see where all my old stories still wanted to be in the experience.

What was the second moment?

That came three years later. I was actually sitting on your couch in your house. I’d had an encounter with an energy of an old relationship, and the encounter brought up a bunch of grief, brought up a lot of pain and activation and frustration. And I was like, I don’t want to feel like this like. Whatever it is that I am holding on to in such a way that it is causing me this kind of suffering—I want to be released from it.

Can I let me go?

I felt this knowing: your path is a spiritual path, Sonya. I had all kinds of stories about what that meant. I had the story that it meant I was going to become a monk. I was going to have to give up so many things. And I was like, I don’t want to. I could feel all the resistance around it. I heard very clearly what there is to do. I’m being asked to say yes to this path. I sat on your couch and I said, fine. Fine! I surrender to the path that spirit has for me. I say yes to this path.

It was as if for three years life had been dragging me like a screaming toddler in the mall. And instantly I felt like I stood up and I had my own sense of my autonomy. Some part of my own internal dignity came back when I chose to stand up and walk with what life was, what life had already clearly said. The suffering instantly left.

What changed in the aftermath of those moments?

A few days later, I was also with you, and some person pulled out in front of us and nearly T-boned us. I put my arm out, and I just said to that person, “May you get where you’re going safely.” Then I got to the Airbnb where I was staying, and there was all this stuff that I normally would have been really activated by it. And I just was like, Oh, that’s what it is! There were just all these tiny moments where the way I’m responding is so different than the me that I am used to.

I sent an email to the Airbnb host to let them know some things were missing. There is a version of Sonya that would have sent it with irritation that I had to send it at all, and with a sort of manipulation, like, let me pretend to be nice, so that I can get what I need. But I felt this purity of response.

I had the experience of knowing that every experience I ever had in life was so that I could have that moment. Every heartache, every ended relationship, every death, every single moment was so that I could write that email and be like, I have nothing to strategize or manipulate for, because everything that is life is present for me.

So what have you had to give up?

All of old Sonya. All of those orientations and adaptations that you asked me about at the beginning of this conversation: the identity of Sonya the hustler, the identity of Sonya the strategizer, the identity of Sonya the caretaker, the identity of Sonya the smart girl. Every version that I had created in response to trying to extract my needs from life had to fall away. Some of them were versions that I really loved. There’s Sonya the personality that I had to give up. In some ways that is to give up Sonya and to simply be.

Do you feel like this is the beginning of an unfolding? Where are you in the becoming? And who are you becoming?

I don’t have the same relationship to time, to future that I used to have—the idea that there is some place I’m trying to get. So becoming is however it is that life will unfold in whatever other moments there will be. But I don’t have any investment. Or I just don’t have the illusion that I have some control over that anymore.

What is one thing you’d suggest to those who are looking towards their own awakening?

I currently am in a daily meditation practice, which is really essential for me to clear mind chatter. It wants to come in and reinstate certain illusions. It wants to be like, Oh, no, remember, we actually do have control here. So meditation helps me come back to presence along the journey.

I had to learn to hear differently. In the beginning of this process, I was given things that at the time were scary, like auditory messages. In our societal context, people tell you you’re crazy and you go to a hospital. Thank goodness that I had a therapist who is also a spiritual practitioner, who was able to tell me you’re not crazy, Sonya. You’re receiving guidance. What does it look like to surrender to the guidance you’re receiving?

So I recommend a daily practice. Ask yourself, what is your daily practice that helps you hear?

About the Contributors

adrienne maree brown grows healing ideas in public through her multi-genre writing, music, and podcasts. Informed by twenty-five years of movement facilitation, somatics, Octavia E. Butler scholarship, and her work as a doula, adrienne has nurtured Emergent Strategy, Pleasure Activism, Radical Imagination, and Transformative Justice as ideas and practices for transformation. She is the author/editor of seven published texts and the founder of the Emergent Strategy Ideation Institute, where she is now the writer-in-residence.

Sonya Renee Taylor is a New York Times best-selling author; world-renowned activist and thought leader on racial justice, body liberation, and transformational change; international award-winning artist; and founder of The Body Is Not an Apology (TBINAA), a global digital media and education company exploring the intersections of identity, healing, and social justice through the framework of radical self-love. Sonya is the author of seven books, including The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self Love. www.sonyareneetaylor.com

The founder of the Algorithmic Justice League shares how human bias shapes machine learning

To train a machine learning model to respond to a pattern like the perceived gender of a face, one approach is to provide labeled training data. The labels represent what machine learning researchers call “ground truth.” Truth as a concept is slippery. For thousands of years humans have debated what is true, whether in courts, philosophers’ chairs, labs, political rallies, public forums, the playground, or when looking into mirrors—“Objects are closer than they appear.”

Scientists have argued for objective truth that is uncovered through experimentation, yet science does not escape human bias and prejudice. Feminist scholars have long pointed out how Western ways of knowing, shaped by patriarchy, attempt to erase the standpoint of the observer, taking a godlike, omniscient, and detached view. However, our standpoint, where we are positioned in society, and our cultural and social experiences shape how we share and interpret our observations. Acknowledging that there is subjectivity to perceived truths brings some humility to observations and the notion of partial truths. The elephant can be perceived as many things depending on whether you touch the tail, the leg, or the trunk.

This is not to say all interpretations are valid, particularly when looking at physical phenomena. Regardless of your acceptance of physical laws, gravity and the knowledge engineers have gained about aerodynamics influence how we build airplanes. In the world of machine learning, the arbiters of ground truth—what a model is taught to be the correct classification of a certain type of data—are those who decide which labels to apply and those who are tasked with applying those labels to data. Both groups bring their own standpoint and understanding to the process. Both groups are exercising the power to decide. Decision-making power is ultimately what defines ground truth. Human decisions are subjective.

The classification systems I or other machine learning practitioners select, modify, inherit, or expand to label a dataset are a reflection of subjective goals, observations, and understandings of the world. These systems of labeling circumscribe the world of possibilities and experience for a machine learning model, which is also limited by the data available. For example, if you decide to use binary gender labels—male and female—and use them on a dataset that includes only the faces of middle-aged white actors, the system is precluded from learning about intersex, trans, or nonbinary representations and will be less equipped to handle faces that fall outside its initial binary training set. The classification system erases the existence of those groups not included in it. It can also reify the groups so that if the most dominant classification of gender is presented in the binary male and female categorization, over time that binary categorization becomes accepted as “truth.” This “truth” ignores rich histories and observations from all over the world regarding gender that acknowledge third-gender individuals or more fluid gender relationships.

When it comes to gender classification systems, the gender labels being used make an inference about gender identity, how an individual interprets their own gender in the world. A computer vision system cannot observe how someone thinks about their gender, because the system is presented only with image data. It’s also true that how someone identifies with gender can change over time. In computer vision that uses machine learning, what machines are being exposed to is gender presentation, how an individual performs their gender in the way they dress, style their hair, and more. Presented with examples of images that are labeled to show what is perceived as male and as female, systems are exposed to cultural norms of gender presentation that can be reflected in length of hair, clothing, and accessories.

Some systems use geometric-based approaches, not appearance-based approaches, and have been programmed based on the physical dimensions of a human face. The scientific evidence shows how sex hormones can influence the shape of a face. Testosterone is observed to lead to a broader nose and forehead—but there are other factors that may lead to a particular nose or forehead shape, so what may be true for faces in a dataset of parliamentarians for Iceland does not necessarily apply to a set of actual faces from Senegal. Also, over time the use of geometric approaches for analyzing faces has been shown to be less effective than the appearance-based models that are learned from large labeled datasets. Coding all the rules for when a nose-to-eye-to-mouth ratio might be that of someone perceived as a woman or biologically female is a daunting task, so the machine learning approach has taken over. But this reliance on labeled data introduces its own challenges.

The representation of a concept like gender is constrained by both the classification system that is used and the data that is used to represent different groups within the classification. If we create a dataset to train a system on binary gender classification that includes only the faces of middle-aged white actors, that model is destined to struggle with gendering faces that do not resemble those in the training set. In the world of computer vision, we find that systems trained on adult faces often struggle with the faces of children, which are changing at a rapid pace as they grow and are often absent from face datasets.

The point remains: For machine learning models data is destiny, because the data provides the model with the representation of the world as curated by the makers of the system. Just as the kinds of labels that are chosen reflect human decisions, the kind of data that is made available is also a reflection of those who have the power to collect and decide which data is used to train a system. The data that is most readily available often is used out of convenience. It is convenient for Facebook to use data made available through user uploads. It is convenient for researchers to scrape the internet for data that is publicly posted. Google and Apple rely on the use of their products to amass extremely valuable datasets, such as voice data that can be collected when a user speaks to the phone to do a search. When ground truth is shaped by convenience sampling, grabbing what is most readily available and applying labels in a subjective manner, it represents the standpoint of the makers of the system, not a standalone objective truth.

A major part of my work is to dissect AI systems and show precisely how they can become biased. My early explorations taught me the importance of going beyond technical knowledge, valuing cultural knowledge, and questioning my own assumptions. We cannot assume that just because something is data driven or processed by an algorithm it is immune to bias. Labels and categories we may take for granted need to be interrogated. The more we know about the histories of racial categorization, the more we learn about how a variety of cultures approach gender, the easier it is to see the human touch that shapes AI systems. Instead of erasing our fingerprints from the creation of algorithmic systems, exposing them more clearly gives us a better understanding of what can go wrong, for whom, and why. AI reflects both our aspirations and our limitations. Our human limitations provide ample reasons for humility about the capabilities of the AI systems we create. Algorithmic justice necessitates questioning the arbiters of truth, because those with the power to build AI systems do not have a monopoly on truth.

Excerpted from the book UNMASKING AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines by Joy Buolamwini. Copyright © 2023 by Joy Buolamwini. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

About the Contributor

Dr. Joy Buolamwini is the founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, a groundbreaking researcher, and a renowned speaker. Her writing has been featured in publications such as Time, the New York Times, Harvard Business Review, and The Atlantic. As the Poet of Code, she creates art to illuminate the impact of artificial intelligence on society and advises world leaders on preventing AI harms. She is the recipient of numerous awards, and her MIT research on facial recognition technologies is featured in the Emmy-nominated documentary Coded Bias.

About the Artwork

The artist who created this image used a partial prompt in Midjourney, an app that uses generative AI to convert language prompts into images. Her partial prompt was /their gender is incomprehensible:: whimsical eccentric 👂costume, spectrum of light, cinematic, absurd surreal photography, kodak porta. The hearing aid emoji is a kind of nonsense placeholder. Midjourney doesn’t understand it, so the 👂 encourages creative ideas versus realistic images. An alternative would be a nonsense word like “dfvnkfc.”

Image Credit

K. Whiteford is an emerging AI artist located in Maryland. She seamlessly fuses absurd surrealism with whimsical beauty in her AI art creations. Through her Instagram platform, she documents her captivating journey in the realm of artificial intelligence artistry. @AIinTheKitchen

A personal story about a radical shift in perspective

As an anthropologist and ethnographer, Huatse Gyal tells the stories of people whose lives are often overlooked. He was born and raised in a nomadic community in the Amdo region of Tibet, so his story might have easily been lost as well. But Huatse was academically gifted and embarked on what he refers to as an “uncommon” educational trajectory, becoming one of the first in his community to attend boarding school and college. His path was different than most, and it wasn’t always easy. The people around him often discriminated against nomads based on their darker skin and stereotypes of being “backwards” or even “stupid.” Huatse encountered such discrimination in middle school, and as a young person it was hard not to internalize it.

When he began taking classes in anthropology, the concept of cultural relativism—the idea that no culture is better or worse, so there’s no hierarchy of inferiority or superiority—resonated with him. He began to understand how internalizing an externally imposed narrative can lead to harmful consequences and keep us tethered to the past. “This idea of cultural relativism and anthropology really emancipated my way of thinking. That was a moment in my life when I managed to reframe my experience and negative ideas of nomads that made me think there was something wrong with me,” Huatse says. His studies became a way for him to understand his life and commit his research to helping nomads and the Tibetan people. Though he moved to the United States to attend college and graduate school, “going farther and farther away from my homeland,” the Tibetan Plateau remains the focus of his research, as he makes connections between indigenous Tibetan communities and those in other parts of the world.

“My parents were nomads,” Huatse says, “but I’m not a nomad in the sense that I no longer raise animals. My profession is teaching, so I have had to release and update my understanding of what it means to be a nomad.” For Huatse, a nomad, as writer Sherman Alexie said in The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, refers to people who are always in search of good grass and good land for the animals. The lifestyle is not easy, but he sees similarities in what he does now. The commonality is to be resilient. “We need to release our attachment to a past or to a sense of loss at the core of our existence. For me, now going into different countries or being in the United States and teaching is akin to the search for good grass in the sense that, as a scholar and a teacher, I’m trying to find a greener intellectual space where I can flourish and help many students.”

About the Contributors

Dr. Huatse Gyal is an anthropologist, writer, filmmaker, and assistant professor of anthropology at Rice University. His work often focuses on the lands and peoples of Tibet.

Howard Kaplan is an editor and writer who helped found Spiral magazine in 2017. He currently works at the Smithsonian and divides his time between Washington, DC, and New York City.

Image Credit

IMAGINE (a.k.a. Sneha Shrestha) is a Nepali artist who incorporates her native language and the aesthetics of Sanskrit scriptures into her work. Her art has been featured in several exhibitions, and her public walls appear across the world from Kathmandu to Boston. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, recently acquired her painting Home416, making her the first contemporary Nepali artist to be part of the museum’s collection. Sneha received her master’s from Harvard University.

The Buddhist concept of non-attachment conveys a transformative reorientation

For many people, the Buddhist concept of non-attachment might initially seem perplexing, or even off-putting. The English term “non-attachment” can give the misleading impression that we should not enjoy anything, or worse, that we are supposed to cultivate indifference or disconnection. But for Buddhists, non-attachment actually conveys the opposite: a transformative reorientation of ourselves and our relationships, an opening up to love and compassion without limit. Indeed, according to Buddhist thinkers past and present, without understanding and practicing non-attachment, we are unable to experience the true enjoyment and connection that we long for. Ultimately, non-attachment in the Buddhist sense reveals the joyful freedom of knowing reality as it really is.

To understand why Buddhists describe non-attachment as an essential and liberating practice, it can be helpful to start with non-attachment’s inverse: the ordinary, addictive way we habitually go about our lives. Think about the moment you wake up each day: Do you stretch? Wish for more sleep? Gulp coffee or tea? Maybe you think about what you’ll do at work or how you hope to see this person, avoid that one, receive a compliment, avoid criticism. Whatever our daily routine, we all have the habit of reaching for experiences we like and pushing away those that we don’t. We are continually hoping for more of this, less of that, in a constant stream of mental activity that a famous Chan Buddhist text calls “picking and choosing.”

Buddhist writers and teachers across the centuries have had a lot to say about the inner process of this picking and choosing. According to Buddhist sources, we ordinarily operate in the endless grip of attachment, understood as a core aspect of how we—and all living beings—relate to our lives. (The English word “attachment” can translate a range of Buddhist terms related to grasping, craving, and desire, such as taṇhā, lobha, and rāga in Sanskrit and Pāli, and chags pa, ’dod chags, and ’dod pa in Tibetan.) Buddhist writers point out that we often think if we could just arrange circumstances to our liking, we would be happy, safe, and problem-free. But the push-pull of our grasping mind continually fails to deliver. Indeed, the relentless grind of attachment and its inseparable twin, aversion, are fundamental aspects of what the Buddha Shakyamuni described as dukkha, the suffering or “dis-ease” that pervades all our ordinary perceptions and experiences.

The nineteenth-century eastern Tibetan Buddhist master Dza Paltrul Rinpoche famously compared our attachment-oriented pursuit of pleasure to licking honey off a knife. We taste sweet honey, but at the exact same moment, the blade slices our tongue. Although we think our attachments will bring us what we want, our attachment contaminates every pleasure with a wound. And the problems with attachment don’t stop with how we hurt or disappoint ourselves. Buddhist teachers say that attachment distorts all our relationships, ironically leading us to subtly center ourselves even when we most wish to be present with others. Attachment gives rise to poisonous emotions like greed, hatred, and jealousy, and compromises our availability for ethical and loving relationships.

As described by Buddhist teachers like Paltrul Rinpoche, our attachment to our own preferences and storylines ultimately reveals a still-deeper form of grasping—the clutching at self-identity that fuels all our suffering. This subtle attachment to self-identity is tied to our ignorance, or more accurately, our miscognition of reality, the miscognition that Buddhists identify as the root “poison” standing between us and enlightenment. Our miscognition is to think we exist as a separate and unchanging self, and then we grab tightly onto the private, isolated self that we think we are. Yet in actuality, as Buddhist thinkers like Paltrul explain, this presumed egocentric self is not how we exist at all. In reality, we are interdependent with all things in an infinitely dynamic relational web of mutual connection and transformation.

At the most basic level then, Buddhist ideas and practices of non-attachment are about freeing ourselves from the grasping states of mind that reduce all relations and events to the ego, trapping us in the closed circle of me and mine, and binding us in a deluded relation to the world. All Buddhist practices of non-attachment turn out to be on some level about making a shift in our awareness: giving ourselves the gift of freedom from our stories about ourselves.

Buddhist techniques for cultivating non-attachment include many methods for working with the body, with social life and relationships, and with the mind and emotions in meditation, ritual, and devotional practice. Bodily and social techniques for developing non-attachment can include a range of renunciant lifestyles and many kinds of vows, including the five vows of lay practitioners and the more detailed vows of monks and nuns. Many traditional ways of teaching and practicing non-attachment begin with material and bodily forms of renunciation and build on these as a foundation for developing a deeper non-attachment to underlying conceptions of self.